Contents

Articles

2024

2023

- Mute @channel & @here notifications in Slack

- A guide to raising better support requests

- Ask Jason: How should we manage security and/or OS updates for our devices?

- Pixel 8 series launches with 7 years of software support

- Android's work profile behaviour has been reverted in 14 beta 5.3

- Fairphone raises the bar with commitment to Android updates

- Product files: The DoorDash T8

- Android's work profile gets a major upgrade in 14

- Google's inactive account policy may not impact Android Enterprise customers

- Product files: Alternative form factors and power solutions

- What's new in Android 14 for enterprise

- Introducing Micro Mobility

- Android Enterprise: A refresher

2022

- What I'd like to see from Android Enterprise in 2023

- Thoughts on Android 12's password complexity changes

- Google Play target API requirements & impact on enterprise applications

- Sunsetting Discuss comment platform

- Google publishes differences between Android and Android Go

- Android Go & EMM support

- Relaunching bayton.org

- AER dropped the 3/5 year update mandate with Android 11, where are we now?

- I made a bet with Google (and lost)

2020

- Product files: Building Android devices

- Google announce big changes to zero-touch

- VMware announces end of support for Device Admin

- Google launch the Android Enterprise Help Community

- Watch: An Android Enterprise discussion with Hypergate

- Listen again: BM podcast #144 - Jason Bayton & Russ Mohr talk Android!

- Google's Android Management API will soon support COPE

- Android Enterprise in 11: Google reduces visibility and control with COPE to bolster privacy.

- The decade that redefined Android in the enterprise

2019

- Why Intune doesn't support Android Enterprise COPE

- VMware WS1 UEM 1908 supports Android Enterprise enrolments on closed networks and AOSP devices

- The Bayton 2019 Android Enterprise experience survey

- Android Enterprise Partner Summit 2019 highlights

- The Huawei ban and Enterprise: what now?

- Dabbling with Android Enterprise in Q beta 3

- Why I moved from Google WiFi to Netgear Orbi

- I'm joining Social Mobile as Director of Android Innovation

- Android Enterprise in Q/10: features and clarity on DA deprecation

- MWC 2019: Mid-range devices excel, 5G everything, form-factors galore and Android Enterprise

- UEM tools managing Android-powered cars

- Joining the Android Enterprise Experts community

- February was an interesting month for OEMConfig

- Google launch Android Enterprise Recommended for Managed Service Providers

- Migrating from Windows 10 Mobile? Here's why you should consider Android

- AER expands: Android Enterprise Recommended for EMMs

- What I'd like to see from Android Enterprise in 2019

2018

- My top Android apps in 2018

- Year in review: 2018

- MobileIron Cloud R58 supports Android Enterprise fully managed devices with work profiles

- Hands on with the Huawei Mate 20 Pro

- Workspace ONE UEM 1810 introduces support for Android Enterprise fully managed devices with work profiles

- G Suite no longer prevents Android data leakage by default

- Live: Huawei Mate series launch

- How to sideload the Digital Wellbeing beta on Pie

- How to manually update the Nokia 7 Plus to Android Pie

- Hands on with the BQ Aquaris X2 Pro

- Hands on with Sony OEMConfig

- The state of Android Enterprise in 2018

- BYOD & Privacy: Don’t settle for legacy Android management in 2018

- Connecting two Synologies via SSH using public and private key authentication

- How to update Rsync on Mac OS Mojave and High Sierra

- Intune gains support for Android Enterprise COSU deployments

- Android Enterprise Recommended: HMD Global launch the Nokia 3.1 and Nokia 5.1

- Android Enterprise Partner Summit 2018 highlights

- Live: MobileIron LIVE! 2018

- Android Enterprise first: AirWatch 9.4 lands with a new name and focus

- Live: Android Enterprise Partner Summit 2018

- Samsung, Oreo and an inconsistent Android Enterprise UX

- MobileIron launch Android Enterprise work profiles on fully managed devices

- Android P demonstrates Google's focus on the enterprise

- An introduction to managed Google Play

- MWC 2018: Android One, Oreo Go, Android Enterprise Recommended & Android Enterprise

- Enterprise ready: Google launch Android Enterprise Recommended

2017

- Year in review: 2017

- Google is deprecating device admin in favour of Android Enterprise

- Hands on with the Sony Xperia XZ1 Compact

- Moto C Plus giveaway

- The state of Android Enterprise in 2017

- Samsung launched a Note 8 for enterprise

- MobileIron officially supports Android Enterprise QR code provisioning

- Android zero-touch enrolment has landed

- MobileIron unofficially supports QR provisioning for Android Enterprise work-managed devices, this is how I found it

- Hands on with the Nokia 3

- Experimenting with clustering and data replication in Nextcloud with MariaDB Galera and SyncThing

- Introducing documentation on bayton.org

- Goodbye Alexa, Hey Google: Hands on with the Google Home

- Restricting access to Exchange ActiveSync

- What is Mobile Device Management?

- 8 tips for a successful EMM deployment

- Long-term update: the fitlet-RM, a fanless industrial mini PC by Compulab

- First look: the FreedomPop V7

- Vault7 and the CIA: This is why we need EMM

- What is Android Enterprise (Android for Work) and why is it used?

- Introducing night mode on bayton.org

- What is iOS Supervision and why is it used?

- Hands on with the Galaxy TabPro S

- Introducing Nextcloud demo servers

- Part 4 - Project Obsidian: Obsidian is dead, long live Obsidian

2016

- My top Android apps 2016

- Hands on with the Linx 12V64

- Wandera review 2016: 2 years on

- Deploying MobileIron 9.1+ on KVM

- Hands on with the Nextcloud Box

- How a promoted tweet landed me on Finnish national news

- Using RWG Mobile for simple, cross-device centralised voicemail

- Part 3 – Project Obsidian: A change, data migration day 1 and build day 2

- Hands on: fitlet-RM, a fanless industrial mini PC by Compulab

- Part 2 - Project Obsidian: Build day 1

- Part 1 - Project Obsidian: Objectives & parts list

- Part 0 - Project Obsidian: Low power NAS & container server

- 5 Android apps improving my Chromebook experience

- First look: Android apps on ChromeOS

- Competition: Win 3 months of free VPS/Container hosting - Closed!

- ElasticHosts review

- ElasticHosts: Cloud Storage vs Folders, what's the difference?

- Adding bash completion to LXD

- Android N: First look & hands-on

- Springs.io - Container hosting at container prices

- Apple vs the FBI: This is why we need MDM

- Miradore Online MDM: Expanding management with subscriptions

- Lenovo Yoga 300 (11IBY) hard drive upgrade

- I bought a Lenovo Yoga 300, this is why I'm sending it back

- Restricting access to Exchange ActiveSync

- Switching to HTTPS on WordPress

2015

2014

- Is CYOD the answer to the BYOD headache?

- BYOD Management: Yes, we can wipe your phone

- A fortnight with Android Wear: LG G Watch review

- First look: Miradore Online free MDM

- Hands on: A weekend with Google Glass

- A month with Wandera Mobile Gateway

- Final thoughts: Dell Venue Pro 11 (Atom)

- Thoughts on BYOD

- Will 2014 bring better battery life?

- My year in review: Bayton.org

- The best purchase I've ever made? A Moto G for my father

2013

2012

- My Top Android Apps 12/12

- The Nexus 7 saga: Resolved

- Recycling Caps Lock into something useful - Ubuntu (12.04)

- The Nexus 7 saga continues

- From Wows to Woes: Why I won't be recommending a Nexus7 any time soon.

- Nexus7: What you need to know

- Why I disabled dlvr.it links on Facebook

- HTC Sense: Changing the lockscreen icons from within ADW

2011

- Push your Google+ posts to Twitter and Facebook

- Using multiple accounts with Google.

- The "Wn-R48" (Windows on the Cr-48)

- Want a Google+ invite?

- Publishing to external sources from Google+

- Dell Streak review. The Phone/Tablet Hybrid

- BlueInput: The Bluetooth HID driver Google forgot to include

- Pushing Buzz to Twitter with dlvr.it

- Managing your social outreach with dlvr.it

- When Awe met Some. The Cr-48 and Gnome3.

- Living with Google's Cr-48 and the cloud.

- Downtime 23-25/04/2011

- Are you practising "safe surfing"?

- The Virtualbox bug: "Cannot access the kernel driver" in Windows

- Putting tech into perspective

2010

- Have a Google Buzz Christmas

- Root a G1 running Android 1.6 without recovery!

- Windows 7 display issues on old Dell desktops

- Google added the Apps flexibility we've been waiting for!

- Part I: My 3 step program for moving to Google Apps

- Downloading torrents

- Completing the Buzz experience for Google Maps Mobile

- Quicktip: Trial Google Apps

- Quicktip: Save internet images fast

- Turn your desktop 3D!

- Part III - Device not compatible - Skype on 3

- Swype not compatible? ShapeWriter!

- Don't wait, get Swype now!

- HideIP VPN. Finally!

- Google enables Wave for Apps domains

- Aspire One touch screen

- Streamline XP into Ubuntu

- Edit a PDF with Zamzar

- Google offering Gmail addresses in the UK

- Google Wave: Revolutionising blogs!

- Hexxeh's Google Chrome OS builds

- Update: Buzz on Windows Mobile

- Alternatives to Internet Explorer

- Wordress 3.0 is coming!

- Skype for WM alternatives

- Browsing on a (data) budget? Opera!

- Buzz on unsupported mobiles

- Buzz on your desktop

- What's all the Buzz?

- Part II: Device not compatible - Skype on 3

- Part I - Device not compatible - Skype on 3

- Dreamscene on Windows 7

- Free Skype with 3? There's a catch..

Change log

Support this site

Product files: The DoorDash T8

Contents

Welcome to Product Files, a series of articles that touch on some of the more interesting aspects of running a product organisation for the last several years.

As this series grows, additional links will show up here:

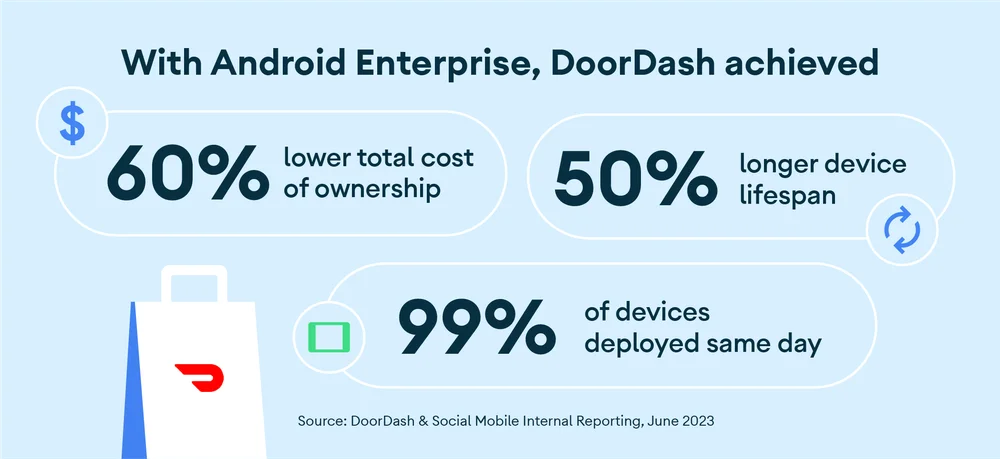

Google recently published a blog post and video by the DoorDash team that covered how the T8, supported by Android Enterprise's suite of management solutions, provided some pretty respectable achievements for them:

As the T8 slowly edges towards the end of its anticipated extended lifecycle and customers begin moving to newer options, I thought I'd take some time in this article to dive a little deeper into the product development of the RHINO T8 and some of the product decisions I made during the development of the tablet that ultimately made it attractive to DoorDash, becoming one of their most-deployed units today.

As I delve into some finer details of T8 development, I'd like to point out this is a device that began its lifecycle in 2019. Some of the features that made it notable at the time are simply par for the course in 2023. That said, I'm still very happy with many of the decisions made that contributed to the device it became.

What is the RHINO T8?

#I touched on the T8 back in 2020 with my Building Android devices article. I'd recommend you take a gander at that if you haven't yet as I provided a good deal of relevant information as to where RHINO came from and the longer-term plans for the brand and ecosystem.

The T8 was part of the first generation of RHINO devices we built from the ground up, something that would not happen again with the recent gen 2 devices as the company opted instead to re-tool products already available in the market through ODM partners.

That said, here it is:

It looks, behaves, and mounts like a standard 8" tablet available from many OEMs in the market today, and especially today in fact, as the ecosystem has filled to the brim with tablets in the last couple of years; far more so than in 2019 when the T8 project kicked off. But that was the intention.

Developing the product

#In strategising what RHINO should be, it was ultimately decided the RHINO brand would be used as a readily-available, widely-applicable showcase of what the company could produce; to act as a springboard into more complex and bespoke projects that could (or not, if bespoke was preferred) leverage these devices as their base. This achieved two objectives:

- Customers could see and feel the build quality of a device in their hands rather than relying on the word of a sales rep. It cannot be understated the difference this has when asking a customer to commit hundreds of thousands of pounds for a product they won't see for 6-9 months.

- For smaller projects the existing tooling and internal designs could be mostly or entirely reused, significantly reducing time to market

One additional benefit for the company was having own-brand stock available for customers simply wanting to buy a device, and as a value-add we were able to pop the company logo of any customer on the tablets for larger orders, giving a bit of organisational customisation most mainstream OEMs don't offer.

The T8 and it's larger sibling, the C10, were the first tablets I launched under the RHINO brand.

Going in to product development for these tablets, the key focus was to develop devices suited to enterprise; this meant considering aspects of use they wouldn't be subject to if consumer owned (and respected), even if MSRP wouldn't eventually be as competitive as an equivalent competing product in the consumer space (think Lenovo, cheaper Samsung tablets, etc). This mindset drove some key requirements for the device:

- Ease of repair

- Tough and resistant to unfriendly usage

- Repellent to moist &/ corrosive environments

- Long term component support

- Resistant to battery ageing

Again, there's nothing groundbreaking here, and OEMs at the time were well-versed in similar requirements for their own offerings (H/T Zebra, Honeywell, Panasonic, etc), but almost across the board they were rugged devices and didn't aim to target the pro-sumer hybrid of consumer device with enterprise features.

But what does this mean in terms of product decisions?

Ease of repair

#Some of the earliest samples and reference products that came from our manufacturing partner during initial stages of development painted a stark picture of what cheap hardware looked like when the only goal is maximising profit:

- Glue blobs galore

- Soldered components

- Single-use clasps and anchors in the housing that would wear out after one to two disassembles of the unit, which was very easy to pull apart

- Loose wiring

- Cheap CMF (colour, materials, finish)

- Zero modularity

- .. and so on

I've pulled apart Android devices (amongst others) aplenty over the years and have seen all of these in use in excess. These devices develop faults and unless you're willing to pull out a soldering iron they become paperweights. By comparison, the exposure I've had to what flagship OEMs have done for internal design - especially thanks to channels like JerryRigEverything and his passion for tearing devices apart so the rest of us don't have to - gave me more than enough inspiration to find a good balance between ease of access, modularisation, and appropriate, re-applicable adhesives.

When it came to starting hardware development for the T8, the first few rounds of E/DVT (Engineering/Design Validation Testing) saw:

- Soldering components swapped for push-fit or lego-style-connectors

- High-wear items like the USB-C port and buttons either reinforced or modularised to their own sub-PCBA for ease of replacement

- Loose wiring replaced by ribbon cabling

- Mild adhesives used for holding the battery in place (with pull tabs) and display to the housing

During this process, I went through more than 10 iterations improving the rigidity of the unit from the first EVT, and ensuring the back wouldn't pop off too easily since it wasn't glued on. Budgetary and time limitations prevented more development in this area; but if I was doing it again today I'd have aimed to make the back cover predominantly secured by screws rather than of clips/clasps, since the latter naturally wears out over time and particularly for customised orders, new printed back panels would have to be made to order when they did wear out, which is a 30-90 day wait.

One final choice was opting not to bond the digitiser and LCD to one another; many OEMs do this with most devices today, which is in effect gluing the touch panel and the display underneath it together to make one item, the display assembly. There are arguments for doing this and it's generally a good thing, not least because the resulting picture can look much better without an air-gap within the assembly, and it also prevents dust and dirt from getting in there. That said, it also increases the cost both in terms of manufacturing cost to pay a factory to do this, but also when it comes time to repair a broken assembly; you're forced to replace the entire thing, or at least purchase the whole assembly, as even if you were to spend the appropriate time with a heat gun to try to separate them, the manufacturer will supply a bonded replacement.

With all changes in place, repairing a T8 became very quick & straightforward to do. Exactly the words repair centres and in-house maintenance teams like to hear when units come in with something broken.

Tough & resistant to unfriendly usage

#In the process of improving repairability, the whole unit benefitted from greater protection from unfriendly usage by, for example, ensuring flex was minimised if the unit was crushed, twisted, or bent. Flex can be a major concern for a screen, since glass doesn't take to it near as well as other materials.

In addition to this I spent several weeks with my team reviewing options for the outer finish of the unit, aiming to find a balance between something that looked decent, but also held up against knocks, scrapes, drops, and so on. On the first few batches of the T8 this was a rubberised finish on the housing, and it held up quite well in the target environments as it:

- Didn't really show marks

- Could be wiped off easily

- Offered better grip when holding it directly

In later production runs with a new manufacturing partner we opted to switch to a textured paint coating instead, offering most of the same benefits but more likely to hold up against harsher cleaning agents and such, as considerable use could see the rubber eventually wear away.

Then there were other design considerations, like the slightly-raised border that surrounds the screen. This is dual-purpose both to absorb shock from drops (along with the rest of the mostly-plastic frame) and keeps the screen ever-so-slightly further from an object that might otherwise impact it.

Repellent to moist &/ corrosive environments

#Knowing the tablet was destined - even during the product development phase with interested customers that predate DoorDash - to land in kitchen and high-humidity environments, but not wanting to fully seal the device for an IP rating (a trade-off for repairability), we dipped the internal components in a moisture-resistant coating.

The tablet doesn't become impervious to moisture with this approach, as dropping it into water or using it during a heavy downpour may allow water to sit within the device and eventually cause a failure, but for humidity, and similar moisture devices may have to deal with, this worked.

Corrosive, in this context, is what is corrosive to a PCBA - impurities, salts, the like. I couldn't save the unit from an acid dip and keep it within a budget!

Long term component support

#Early on in the company's history a partnership was formed with MediaTek, as we pivoted to enterprise MTK's AIoT division became our go-to for chipset selection that guaranteed long-term support & availability. The MT8765 in the T8 is by no means a powerhouse, in fact I think it's fair to say it wasn't the best choice of chipset in retrospect due to the performance issues I've seen over the years with it. For Android Go it would have been absolutely fine, and in truth the T8 would have made for a great Go device given the predominant use-cases for it, but we certified it for full-fat Android in the beginning and stuck it out.

That said, it's taken us from 9.0 to 12, with potentially longer support possible if desired. Since The T8 is coming up on 5 years in-market, that need is simply not there.

Outside the chipset all the standard multi-source component procurement was done by the team accordingly, so we rarely suffered component shortages even during some particularly tumultuous times for the global supply chain in the last few years; even now 4 years later and running another batch of 10s of thousands of units through production component supply has been pretty reliable.

Resistant to battery ageing

#One of the more active requirements, especially from customers coming from consumer tablets they'd had docked to a power supply for 6+months and suffered battery ballooning, was to handle power management intelligently.

What I wanted to be able to facilitate from the get-go was a complete power management solution that allowed customers to:

- Boot & run without a battery connected (when connected to a power cable)

- Bypass the battery and run directly from power cable with the battery installed

- Configure OEMConfig APIs to control this via software, if it wasn't feasible to interface the hardware

Unfortunately this quickly overshot time & budget requirements (but I did take some of this over to the M10p!), so I had to settle for a fully-software smart monitoring solution that would detect for how long the T8 had been plugged in, the voltages and cycles of the battery, and alter the charging profile accordingly. This required engineering coordination between the Android framework folks, kernel folks, and the engineers responsible for the PMIC design.

From a UX perspective, it also introduced some scenarios that customers (or rather, their users who didn't read manuals) raised concerns about. When the tablet had been on charge for more than 24 hours straight for example, we allowed the battery to discharge intentionally to align with the new power profile. Unsurprisingly support tickets did get raised about devices not charging. There were also tickets raised about this solution not kicking in where customers would turn the power off to the tablet when their stores/offices/spaces closed, and back on in the morning; the solution simply wouldn't ever kick in because it wasn't permanently (or >24h) on charge.

So it wasn't infallible, and accordingly we did see some genuine battery failures in the wild, but overall it's been a reasonably insignificant number compared to the number of devices shipped overall.

The Android journey

#This is not so related to DoorDash choosing the T8, but I think it's interesting to cover since it's relevant to the article.

The RHINO promise has been bloat-free, vanilla Android since inception.

Beyond Google apps and a couple of OEM-specific services (activation server, OEMConfig, chipset support), and some OEMConfig APIs, my flavour of Android is as light and clean as it comes.

To achieve this was no insignificant undertaking as working with external engineering houses well-versed in the MediaTek turnkey builds (these are builds of Android the chipset makers offer with integrated support for the chosen chipset. Qualcomm, Rockchip, and others offer the same, often referred to as BSPs.) meant the only option for building Android I could get was to lean on these pre-made builds rather than building from AOSP.

Again as with many things in product development there are pros and cons. The pros for a turnkey/BSP build are normally time to market and little need for configuration. The cons come in the amount of time you choose to dedicate to removing bloat the chipset vendor includes. Engineering apps, battery optimisers, sound enhancers, carrier optimisation apps.. you name it, the vendor has an app for it, and it's likely included. Then come the tweaks to UI and defaults set - Icon shapes, default radio behaviour, navigation setup, and so on.

From the very beginning I built out a version-based requirements doc that combined a mixture of both best practice security and enterprise-friendly defaults, laced with some personal opinions on how Android should look, feel, and behave in line with examples set by Google and other OEMs offering vanilla builds. The turnkey builds were a fair departure from what I'd consider RHINO ready and so there was always a fair amount of work to do, even without custom development of OEMConfig and other bespoke functionalities.

Still with all the reconfiguration required it remained faster than building AOSP from scratch, though given the choice I'd prefer building from AOSP. Swings and roundabouts.

For the T8 we went through this process three times, the latest earlier in 2023 with Android 12. Each major OS build requiring porting of the changes made to the version before it, or setting up again based on the requirements doc from scratch. Upgrading unfortunately isn't much easier than building a version from scratch in my experience, but this could be down to the engineering partners I had available; my experience is understandably limited, and I imagine there's a good amount of investment in build management and development in larger OEMs that would offer a world of difference.

The T8 launched with Android 9.0. 10 was feasible already at the time, but it was considered too new for some more risk-averse in the company and the older, more stable version of Android was chosen for the first products in the RHINO brand. It's understandable in some theory, but on reflection it wasn't a great choice, and had implications throughout the product's lifecycle.

9.0 included a version of Treble that was definitely not close to final, a fixed (as in permanently-set) partition system, and some other less-than-forgiving attributes. It was 10 that introduced the concept of dynamic partitioning, and set the groundwork for substantially more flexibility in how OEMs work with the on-device storage for resizing and repurposing disk partitioning on-the-go in later Android versions. This has been realised in the release of 12 this year for the T8, but given the device isn't planned to see 13, both due to demand and MediaTek's apparent stance on chipset support, the benefit is no longer there.

Because we launched on 9.0, the same partitioning had to be used in 10 to allow an OTA (Over The Air) upgrade. Partitions can always be rewritten with a manual flash of a device, but an OTA update cannot adjust physical partition sizes. If we were launching 10 with a new device (like the M10p) we could have implemented dynamic partitioning, but as we wanted to upgrade from a fixed partition system on an existing device, we had to retain that.

The trouble with fixed partitioning is unless you configure partitions to accommodate larger on-disk sizes later - something you can't scientifically calculate given changes that impact system sizing can't be predicted for the next version of Android, never mind 2 or 3 later - you'll eventually run out of space and can no longer support the upgrade to a newer version without some significant hackery, if possible. This is effectively what happened with the T8, and why we went 9.0 > 10 via OTA, then 12 with a manual flash for existing units, or a preload from factory of 12 for units manufactured in 2023. The upgrade to 11 took the /system partition to a larger minimum size than we could accommodate on the 9.0-specced partition layout, and we deferred upgrading again until necessary.

Another aspect of maintaining an Android product over multiple years is GMS approval. Google sets approval windows for every Android release that state the latest possible time permitted for approving a new release of Android both as a new product, but also as an existing product that's upgrading; the latter has a bit more time since it's already an in-market device that needs to be supported. There are also expiry dates that stipulate the date after which it is not permitted to manufacture new Android devices with an older version of Android, though existing manufactured devices in the field could continue getting updates. These dates also differ based on form factor, Android flavour, and GMS licence (ie. EDLA (enterprise dedicated) devices).

It's a reasonably complex, though not necessarily complicated process.

For Android 10, the expiry date for GMS approval as a tablet on the MADA licence was Dec 2022, that means devices manufactured from January had to preload a newer version of Android from the factory, so 11+.

11 however passed the last date for GMS approval as a LR (launch release, an upgrade) back around August 2022, which meant when DoorDash picked up the phone and requested a brand new, freshly manufactured batch of T8s in late 2022, Android 12 development had to also be undertaken in order to have an approved Android build to put on the tablets in the factory before shipping out.

But what about security patches?

#Security updates are comparatively much simpler to plan and manage than major version releases, on the whole. The T8 has received quarterly security patches since 2019, and will continue to do so into 2024 based on current plans.

The only implication with security updates is when Google stop backporting them. Backporting, to address the assumed question, is where Google will take the patch of a security vulnerability in the current version branch of Android (say, 13 as of August 2023) and undertake the necessary engineering to be compatible with older versions, so 12, 11, 10, before committing it to those version branches respectively.

OEM engineering resources then pick up the patches for the relevant version they're working with, along with patches from component suppliers, chipset vendors, and anyone else pertinent to a specific device, and roll it out into the device tree (source code for the device).

Google will not backport forever, however. There is typically a limit of 3 years per OS version before they cease backporting and instead focus on newer versions of Android.

As an OEM, you then have the choice of:

- Continuing to support an Android version by cherry-picking patches from a newer version of Android and doing the engineering internally to apply to your device

- Or upgrading to a newer version of Android

Manual backporting, as it's referred when the OEM does it after Google stops, can be challenging, especially for smaller OEMs or their engineering parters. I've often struggled to lock in agreements with partner resources, who would almost unanimously rather undertake the task of rolling out a new version of Android than keep the older version secure once Google moves on (either route demanding a reasonable chunk of change to achieve).

This is relevant because while the T8 has received security updates on time and religiously since launch with no action from customers required across 9.0 and 10, backporting for Android 10 officially ended in Feb 2023, and as such the last security update for that version went out to the customer base a couple of months ago. Customers who want to continue to receive security updates for another year will have to manually flash tablets to the latest version.

So to reiterate, launching on 9.0 was not a great decision. Thankfully all projects after the T8/C10 adhered to my mandate for leaning towards the newer versions of Android available to avoid such frustrations re-occurring, and 4 years later newer projects are faring much better.

Not all that bad

#Though the T8's Android journey has been somewhat more challenging, this isn't reflected across all projects I've worked on and devices I've supported. I want to stress it's been mostly enjoyable to support the platform. I enjoy debugging (and squashing!) bugs, writing the release notes, scheduling the OTAs, planning feature drops, building out the OEMConfig (and other solutions) roadmap based on customer needs, and absolutely..

..more than anything..

..requesting bug reports from customers 38 times a day in response to one-sentence support tickets exclaiming something is broken. :).

Wrapping up

#I've covered off a fair bit of my experience bringing the T8 to market from a product development point of view. I naturally haven't touched on everything that went into launching the T8, nor some of the more bespoke requests from DoorDash on customisations they've received over the years to the model, including:

- Hardware revisions configured to local markets/geographies we didn't initially launch into

- Custom hardware configurations (NFC was removed from one revision for a particular use case)

- All of their custom branding and packaging

- Their custom-manufactured accessories (cases, etc)

And many other value-adds that made the T8 the DoorDash T8. But ultimately a springboard from which to jump is what had them Dash through the Door (😁) in the first place, and I'm immeasurably proud of what I and my team achieved as the first major project of a new brand.

Articles

2024

2023

- Mute @channel & @here notifications in Slack

- A guide to raising better support requests

- Ask Jason: How should we manage security and/or OS updates for our devices?

- Pixel 8 series launches with 7 years of software support

- Android's work profile behaviour has been reverted in 14 beta 5.3

- Fairphone raises the bar with commitment to Android updates

- Product files: The DoorDash T8

- Android's work profile gets a major upgrade in 14

- Google's inactive account policy may not impact Android Enterprise customers

- Product files: Alternative form factors and power solutions

- What's new in Android 14 for enterprise

- Introducing Micro Mobility

- Android Enterprise: A refresher

2022

- What I'd like to see from Android Enterprise in 2023

- Thoughts on Android 12's password complexity changes

- Google Play target API requirements & impact on enterprise applications

- Sunsetting Discuss comment platform

- Google publishes differences between Android and Android Go

- Android Go & EMM support

- Relaunching bayton.org

- AER dropped the 3/5 year update mandate with Android 11, where are we now?

- I made a bet with Google (and lost)

2020

- Product files: Building Android devices

- Google announce big changes to zero-touch

- VMware announces end of support for Device Admin

- Google launch the Android Enterprise Help Community

- Watch: An Android Enterprise discussion with Hypergate

- Listen again: BM podcast #144 - Jason Bayton & Russ Mohr talk Android!

- Google's Android Management API will soon support COPE

- Android Enterprise in 11: Google reduces visibility and control with COPE to bolster privacy.

- The decade that redefined Android in the enterprise

2019

- Why Intune doesn't support Android Enterprise COPE

- VMware WS1 UEM 1908 supports Android Enterprise enrolments on closed networks and AOSP devices

- The Bayton 2019 Android Enterprise experience survey

- Android Enterprise Partner Summit 2019 highlights

- The Huawei ban and Enterprise: what now?

- Dabbling with Android Enterprise in Q beta 3

- Why I moved from Google WiFi to Netgear Orbi

- I'm joining Social Mobile as Director of Android Innovation

- Android Enterprise in Q/10: features and clarity on DA deprecation

- MWC 2019: Mid-range devices excel, 5G everything, form-factors galore and Android Enterprise

- UEM tools managing Android-powered cars

- Joining the Android Enterprise Experts community

- February was an interesting month for OEMConfig

- Google launch Android Enterprise Recommended for Managed Service Providers

- Migrating from Windows 10 Mobile? Here's why you should consider Android

- AER expands: Android Enterprise Recommended for EMMs

- What I'd like to see from Android Enterprise in 2019

2018

- My top Android apps in 2018

- Year in review: 2018

- MobileIron Cloud R58 supports Android Enterprise fully managed devices with work profiles

- Hands on with the Huawei Mate 20 Pro

- Workspace ONE UEM 1810 introduces support for Android Enterprise fully managed devices with work profiles

- G Suite no longer prevents Android data leakage by default

- Live: Huawei Mate series launch

- How to sideload the Digital Wellbeing beta on Pie

- How to manually update the Nokia 7 Plus to Android Pie

- Hands on with the BQ Aquaris X2 Pro

- Hands on with Sony OEMConfig

- The state of Android Enterprise in 2018

- BYOD & Privacy: Don’t settle for legacy Android management in 2018

- Connecting two Synologies via SSH using public and private key authentication

- How to update Rsync on Mac OS Mojave and High Sierra

- Intune gains support for Android Enterprise COSU deployments

- Android Enterprise Recommended: HMD Global launch the Nokia 3.1 and Nokia 5.1

- Android Enterprise Partner Summit 2018 highlights

- Live: MobileIron LIVE! 2018

- Android Enterprise first: AirWatch 9.4 lands with a new name and focus

- Live: Android Enterprise Partner Summit 2018

- Samsung, Oreo and an inconsistent Android Enterprise UX

- MobileIron launch Android Enterprise work profiles on fully managed devices

- Android P demonstrates Google's focus on the enterprise

- An introduction to managed Google Play

- MWC 2018: Android One, Oreo Go, Android Enterprise Recommended & Android Enterprise

- Enterprise ready: Google launch Android Enterprise Recommended

2017

- Year in review: 2017

- Google is deprecating device admin in favour of Android Enterprise

- Hands on with the Sony Xperia XZ1 Compact

- Moto C Plus giveaway

- The state of Android Enterprise in 2017

- Samsung launched a Note 8 for enterprise

- MobileIron officially supports Android Enterprise QR code provisioning

- Android zero-touch enrolment has landed

- MobileIron unofficially supports QR provisioning for Android Enterprise work-managed devices, this is how I found it

- Hands on with the Nokia 3

- Experimenting with clustering and data replication in Nextcloud with MariaDB Galera and SyncThing

- Introducing documentation on bayton.org

- Goodbye Alexa, Hey Google: Hands on with the Google Home

- Restricting access to Exchange ActiveSync

- What is Mobile Device Management?

- 8 tips for a successful EMM deployment

- Long-term update: the fitlet-RM, a fanless industrial mini PC by Compulab

- First look: the FreedomPop V7

- Vault7 and the CIA: This is why we need EMM

- What is Android Enterprise (Android for Work) and why is it used?

- Introducing night mode on bayton.org

- What is iOS Supervision and why is it used?

- Hands on with the Galaxy TabPro S

- Introducing Nextcloud demo servers

- Part 4 - Project Obsidian: Obsidian is dead, long live Obsidian

2016

- My top Android apps 2016

- Hands on with the Linx 12V64

- Wandera review 2016: 2 years on

- Deploying MobileIron 9.1+ on KVM

- Hands on with the Nextcloud Box

- How a promoted tweet landed me on Finnish national news

- Using RWG Mobile for simple, cross-device centralised voicemail

- Part 3 – Project Obsidian: A change, data migration day 1 and build day 2

- Hands on: fitlet-RM, a fanless industrial mini PC by Compulab

- Part 2 - Project Obsidian: Build day 1

- Part 1 - Project Obsidian: Objectives & parts list

- Part 0 - Project Obsidian: Low power NAS & container server

- 5 Android apps improving my Chromebook experience

- First look: Android apps on ChromeOS

- Competition: Win 3 months of free VPS/Container hosting - Closed!

- ElasticHosts review

- ElasticHosts: Cloud Storage vs Folders, what's the difference?

- Adding bash completion to LXD

- Android N: First look & hands-on

- Springs.io - Container hosting at container prices

- Apple vs the FBI: This is why we need MDM

- Miradore Online MDM: Expanding management with subscriptions

- Lenovo Yoga 300 (11IBY) hard drive upgrade

- I bought a Lenovo Yoga 300, this is why I'm sending it back

- Restricting access to Exchange ActiveSync

- Switching to HTTPS on WordPress

2015

2014

- Is CYOD the answer to the BYOD headache?

- BYOD Management: Yes, we can wipe your phone

- A fortnight with Android Wear: LG G Watch review

- First look: Miradore Online free MDM

- Hands on: A weekend with Google Glass

- A month with Wandera Mobile Gateway

- Final thoughts: Dell Venue Pro 11 (Atom)

- Thoughts on BYOD

- Will 2014 bring better battery life?

- My year in review: Bayton.org

- The best purchase I've ever made? A Moto G for my father

2013

2012

- My Top Android Apps 12/12

- The Nexus 7 saga: Resolved

- Recycling Caps Lock into something useful - Ubuntu (12.04)

- The Nexus 7 saga continues

- From Wows to Woes: Why I won't be recommending a Nexus7 any time soon.

- Nexus7: What you need to know

- Why I disabled dlvr.it links on Facebook

- HTC Sense: Changing the lockscreen icons from within ADW

2011

- Push your Google+ posts to Twitter and Facebook

- Using multiple accounts with Google.

- The "Wn-R48" (Windows on the Cr-48)

- Want a Google+ invite?

- Publishing to external sources from Google+

- Dell Streak review. The Phone/Tablet Hybrid

- BlueInput: The Bluetooth HID driver Google forgot to include

- Pushing Buzz to Twitter with dlvr.it

- Managing your social outreach with dlvr.it

- When Awe met Some. The Cr-48 and Gnome3.

- Living with Google's Cr-48 and the cloud.

- Downtime 23-25/04/2011

- Are you practising "safe surfing"?

- The Virtualbox bug: "Cannot access the kernel driver" in Windows

- Putting tech into perspective

2010

- Have a Google Buzz Christmas

- Root a G1 running Android 1.6 without recovery!

- Windows 7 display issues on old Dell desktops

- Google added the Apps flexibility we've been waiting for!

- Part I: My 3 step program for moving to Google Apps

- Downloading torrents

- Completing the Buzz experience for Google Maps Mobile

- Quicktip: Trial Google Apps

- Quicktip: Save internet images fast

- Turn your desktop 3D!

- Part III - Device not compatible - Skype on 3

- Swype not compatible? ShapeWriter!

- Don't wait, get Swype now!

- HideIP VPN. Finally!

- Google enables Wave for Apps domains

- Aspire One touch screen

- Streamline XP into Ubuntu

- Edit a PDF with Zamzar

- Google offering Gmail addresses in the UK

- Google Wave: Revolutionising blogs!

- Hexxeh's Google Chrome OS builds

- Update: Buzz on Windows Mobile

- Alternatives to Internet Explorer

- Wordress 3.0 is coming!

- Skype for WM alternatives

- Browsing on a (data) budget? Opera!

- Buzz on unsupported mobiles

- Buzz on your desktop

- What's all the Buzz?

- Part II: Device not compatible - Skype on 3

- Part I - Device not compatible - Skype on 3

- Dreamscene on Windows 7

- Free Skype with 3? There's a catch..