Contents

Articles

2024

2023

- Mute @channel & @here notifications in Slack

- A guide to raising better support requests

- Ask Jason: How should we manage security and/or OS updates for our devices?

- Pixel 8 series launches with 7 years of software support

- Android's work profile behaviour has been reverted in 14 beta 5.3

- Fairphone raises the bar with commitment to Android updates

- Product files: The DoorDash T8

- Android's work profile gets a major upgrade in 14

- Google's inactive account policy may not impact Android Enterprise customers

- Product files: Alternative form factors and power solutions

- What's new in Android 14 for enterprise

- Introducing Micro Mobility

- Android Enterprise: A refresher

2022

- What I'd like to see from Android Enterprise in 2023

- Thoughts on Android 12's password complexity changes

- Google Play target API requirements & impact on enterprise applications

- Sunsetting Discuss comment platform

- Google publishes differences between Android and Android Go

- Android Go & EMM support

- Relaunching bayton.org

- AER dropped the 3/5 year update mandate with Android 11, where are we now?

- I made a bet with Google (and lost)

2020

- Product files: Building Android devices

- Google announce big changes to zero-touch

- VMware announces end of support for Device Admin

- Google launch the Android Enterprise Help Community

- Watch: An Android Enterprise discussion with Hypergate

- Listen again: BM podcast #144 - Jason Bayton & Russ Mohr talk Android!

- Google's Android Management API will soon support COPE

- Android Enterprise in 11: Google reduces visibility and control with COPE to bolster privacy.

- The decade that redefined Android in the enterprise

2019

- Why Intune doesn't support Android Enterprise COPE

- VMware WS1 UEM 1908 supports Android Enterprise enrolments on closed networks and AOSP devices

- The Bayton 2019 Android Enterprise experience survey

- Android Enterprise Partner Summit 2019 highlights

- The Huawei ban and Enterprise: what now?

- Dabbling with Android Enterprise in Q beta 3

- Why I moved from Google WiFi to Netgear Orbi

- I'm joining Social Mobile as Director of Android Innovation

- Android Enterprise in Q/10: features and clarity on DA deprecation

- MWC 2019: Mid-range devices excel, 5G everything, form-factors galore and Android Enterprise

- UEM tools managing Android-powered cars

- Joining the Android Enterprise Experts community

- February was an interesting month for OEMConfig

- Google launch Android Enterprise Recommended for Managed Service Providers

- Migrating from Windows 10 Mobile? Here's why you should consider Android

- AER expands: Android Enterprise Recommended for EMMs

- What I'd like to see from Android Enterprise in 2019

2018

- My top Android apps in 2018

- Year in review: 2018

- MobileIron Cloud R58 supports Android Enterprise fully managed devices with work profiles

- Hands on with the Huawei Mate 20 Pro

- Workspace ONE UEM 1810 introduces support for Android Enterprise fully managed devices with work profiles

- G Suite no longer prevents Android data leakage by default

- Live: Huawei Mate series launch

- How to sideload the Digital Wellbeing beta on Pie

- How to manually update the Nokia 7 Plus to Android Pie

- Hands on with the BQ Aquaris X2 Pro

- Hands on with Sony OEMConfig

- The state of Android Enterprise in 2018

- BYOD & Privacy: Don’t settle for legacy Android management in 2018

- Connecting two Synologies via SSH using public and private key authentication

- How to update Rsync on Mac OS Mojave and High Sierra

- Intune gains support for Android Enterprise COSU deployments

- Android Enterprise Recommended: HMD Global launch the Nokia 3.1 and Nokia 5.1

- Android Enterprise Partner Summit 2018 highlights

- Live: MobileIron LIVE! 2018

- Android Enterprise first: AirWatch 9.4 lands with a new name and focus

- Live: Android Enterprise Partner Summit 2018

- Samsung, Oreo and an inconsistent Android Enterprise UX

- MobileIron launch Android Enterprise work profiles on fully managed devices

- Android P demonstrates Google's focus on the enterprise

- An introduction to managed Google Play

- MWC 2018: Android One, Oreo Go, Android Enterprise Recommended & Android Enterprise

- Enterprise ready: Google launch Android Enterprise Recommended

2017

- Year in review: 2017

- Google is deprecating device admin in favour of Android Enterprise

- Hands on with the Sony Xperia XZ1 Compact

- Moto C Plus giveaway

- The state of Android Enterprise in 2017

- Samsung launched a Note 8 for enterprise

- MobileIron officially supports Android Enterprise QR code provisioning

- Android zero-touch enrolment has landed

- MobileIron unofficially supports QR provisioning for Android Enterprise work-managed devices, this is how I found it

- Hands on with the Nokia 3

- Experimenting with clustering and data replication in Nextcloud with MariaDB Galera and SyncThing

- Introducing documentation on bayton.org

- Goodbye Alexa, Hey Google: Hands on with the Google Home

- Restricting access to Exchange ActiveSync

- What is Mobile Device Management?

- 8 tips for a successful EMM deployment

- Long-term update: the fitlet-RM, a fanless industrial mini PC by Compulab

- First look: the FreedomPop V7

- Vault7 and the CIA: This is why we need EMM

- What is Android Enterprise (Android for Work) and why is it used?

- Introducing night mode on bayton.org

- What is iOS Supervision and why is it used?

- Hands on with the Galaxy TabPro S

- Introducing Nextcloud demo servers

- Part 4 - Project Obsidian: Obsidian is dead, long live Obsidian

2016

- My top Android apps 2016

- Hands on with the Linx 12V64

- Wandera review 2016: 2 years on

- Deploying MobileIron 9.1+ on KVM

- Hands on with the Nextcloud Box

- How a promoted tweet landed me on Finnish national news

- Using RWG Mobile for simple, cross-device centralised voicemail

- Part 3 – Project Obsidian: A change, data migration day 1 and build day 2

- Hands on: fitlet-RM, a fanless industrial mini PC by Compulab

- Part 2 - Project Obsidian: Build day 1

- Part 1 - Project Obsidian: Objectives & parts list

- Part 0 - Project Obsidian: Low power NAS & container server

- 5 Android apps improving my Chromebook experience

- First look: Android apps on ChromeOS

- Competition: Win 3 months of free VPS/Container hosting - Closed!

- ElasticHosts review

- ElasticHosts: Cloud Storage vs Folders, what's the difference?

- Adding bash completion to LXD

- Android N: First look & hands-on

- Springs.io - Container hosting at container prices

- Apple vs the FBI: This is why we need MDM

- Miradore Online MDM: Expanding management with subscriptions

- Lenovo Yoga 300 (11IBY) hard drive upgrade

- I bought a Lenovo Yoga 300, this is why I'm sending it back

- Restricting access to Exchange ActiveSync

- Switching to HTTPS on WordPress

2015

2014

- Is CYOD the answer to the BYOD headache?

- BYOD Management: Yes, we can wipe your phone

- A fortnight with Android Wear: LG G Watch review

- First look: Miradore Online free MDM

- Hands on: A weekend with Google Glass

- A month with Wandera Mobile Gateway

- Final thoughts: Dell Venue Pro 11 (Atom)

- Thoughts on BYOD

- Will 2014 bring better battery life?

- My year in review: Bayton.org

- The best purchase I've ever made? A Moto G for my father

2013

2012

- My Top Android Apps 12/12

- The Nexus 7 saga: Resolved

- Recycling Caps Lock into something useful - Ubuntu (12.04)

- The Nexus 7 saga continues

- From Wows to Woes: Why I won't be recommending a Nexus7 any time soon.

- Nexus7: What you need to know

- Why I disabled dlvr.it links on Facebook

- HTC Sense: Changing the lockscreen icons from within ADW

2011

- Push your Google+ posts to Twitter and Facebook

- Using multiple accounts with Google.

- The "Wn-R48" (Windows on the Cr-48)

- Want a Google+ invite?

- Publishing to external sources from Google+

- Dell Streak review. The Phone/Tablet Hybrid

- BlueInput: The Bluetooth HID driver Google forgot to include

- Pushing Buzz to Twitter with dlvr.it

- Managing your social outreach with dlvr.it

- When Awe met Some. The Cr-48 and Gnome3.

- Living with Google's Cr-48 and the cloud.

- Downtime 23-25/04/2011

- Are you practising "safe surfing"?

- The Virtualbox bug: "Cannot access the kernel driver" in Windows

- Putting tech into perspective

2010

- Have a Google Buzz Christmas

- Root a G1 running Android 1.6 without recovery!

- Windows 7 display issues on old Dell desktops

- Google added the Apps flexibility we've been waiting for!

- Part I: My 3 step program for moving to Google Apps

- Downloading torrents

- Completing the Buzz experience for Google Maps Mobile

- Quicktip: Trial Google Apps

- Quicktip: Save internet images fast

- Turn your desktop 3D!

- Part III - Device not compatible - Skype on 3

- Swype not compatible? ShapeWriter!

- Don't wait, get Swype now!

- HideIP VPN. Finally!

- Google enables Wave for Apps domains

- Aspire One touch screen

- Streamline XP into Ubuntu

- Edit a PDF with Zamzar

- Google offering Gmail addresses in the UK

- Google Wave: Revolutionising blogs!

- Hexxeh's Google Chrome OS builds

- Update: Buzz on Windows Mobile

- Alternatives to Internet Explorer

- Wordress 3.0 is coming!

- Skype for WM alternatives

- Browsing on a (data) budget? Opera!

- Buzz on unsupported mobiles

- Buzz on your desktop

- What's all the Buzz?

- Part II: Device not compatible - Skype on 3

- Part I - Device not compatible - Skype on 3

- Dreamscene on Windows 7

- Free Skype with 3? There's a catch..

Support this site

What is Play Auto Install (PAI) in Android and how does it work?

Contents

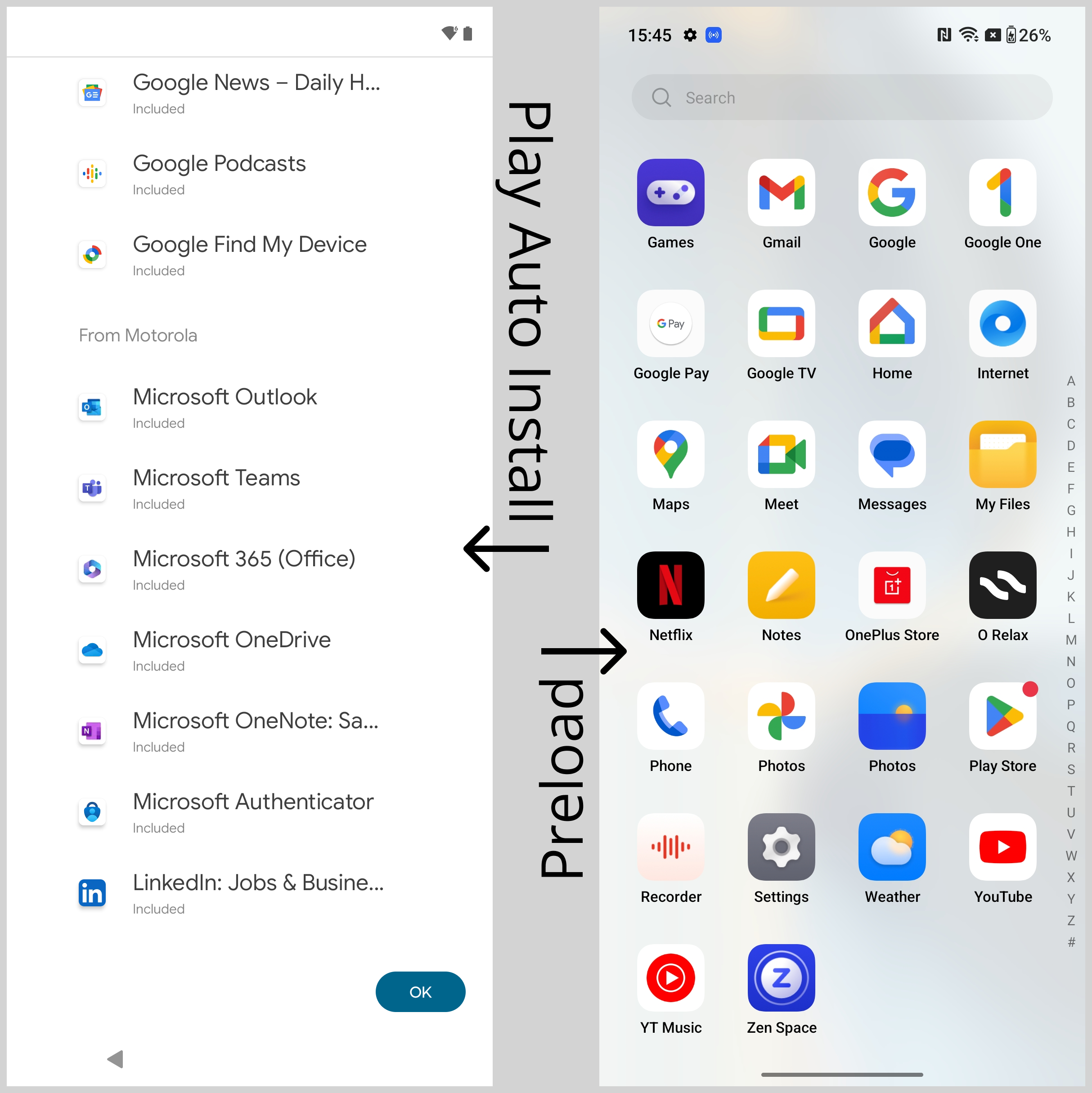

If you have set up a modern Android device, may have come across the list of apps offered by your device just before you finish setup. This is referred to as Play Auto Install and is available to OEMs building certified Android devices.

The list of recommended and required applications suggests (or mandates) a selection of applications the OEM, carrier, or Google consider useful for your Android experience, and is an alternative to the other standard approach of just preloading APKs into the system image.

The way the apps are presented can differ, sometimes they're pre-checked with the option to deselect as desired, while sometimes they may be selected (or "included") with no means of de-selecting. The latter you'll often see with the suite of Google applications, but can equally be set as mandatory by the OEM as shown by Motorola's push of Microsoft apps (I promptly uninstalled) above.

So what's PAI? And why does it matter?

History

#Since the dawn of time, application developers have sought means to ensure their applications and services are put in front of as many people as possible. Whether through ads in your browser or app store, partnerships with other developers or vendors to promote complimentary solutions, or the many other ways the general public has sponsored content thrust at their collective faces in modern society.

At some point this found its way into the sacred space of your personal device. I wouldn't be able to pinpoint exactly when, but an OEM in the early days of Android decided they'd like to offer the option of preloading the applications of partners into the builds of their Android devices, and forever diverged the platform from other popular mobile operating systems in the ecosystem to turn Android into a mule for bloatware.

From that point on devices shipped with applications preloaded within the OEM build of Android; often in the /system partition too (though less common as time went on, and partitioning changed in Android overall), which would not only eat into the available partition size defined by the OEM, but do so in a way that was non-removable by users, and with different builds destined for different regions, carriers, or otherwise including differing applications in response to the target market accordingly it added additional complexity to the build processes overall.

It did however as mentioned guarantee the applications preloaded could not be removed (unless apps would occasionally be found in the /data partition where they would be removable), and in some cases OEMs would go as far as preventing applications from being disabled as well, the only available means of "removing" a preloaded application that a user would not want on their device.

This still happens today, but it feels less prevalent now than back then. That's not a data-driven statement, don't quote me.

Drawbacks

#Aside from the obvious user distaste for bloatware, for which the ecosystem has mostly come to terms with as a fact an Android device is likely to ship with apps and services they don't want; particularly in the case of carrier-subsidised devices where bloat is prolific? In the context of PAI there are known drawbacks to preloading apps in the system build:

It uses space - As mentioned above, but a little more detail: You can argue a 10MB Android app isn't making all that difference to the device as a whole, but again pre 9.0, where partitions were defined manually, there were real implications to this. Apps grow over time, and even if the preloaded app does not, it shares the partition with system applications, the GMS suite of apps, and more. Once a device is out in the wild the partitions can't be changed (pre-10!), and every OTA delivered must meet the size requirement of the partition it'll be installed on. From Android 10 this limitation went away, though you're still taking space from the user.

A real example of this was with the original 8" tablet I worked to bring to market way back in 2020 on Android 9.0. Although the 32GB of on-board storage was plentiful, the system partitions were sized conservatively to provide more available storage for customers. This was fine for the first year or two, but with the Android 10 upgrade almost all of the available space was exhausted. As updates through the year were pushed, and the GMS core suite of apps were updated with newer, larger APKs, it shrunk to the point an Android 11 upgrade would not have been feasible.

Now again this is in the context of Android 9.0, where partitions were fixed, Android 10 introduced dynamic partitions further improved in 11, but this could not be leveraged on a device that shipped with fixed partitions. To adjust the partition layout would have required devices are sent in for repair, flashed with a version of Android 10 that implemented dynamic partitioning, and then 11, 12, 13, etc would have worked absolutely fine, at the ongoing cost of shrinking user-available storage (but still nothing compared to the gargantuan sizes of Android builds from the likes of Samsung!).

I didn't ship bloat with my hardware, opting instead to lean on PAI to offer them up, which will be covered more below. I did however have a couple of system applications developed; an activation service, and an OEMConfig app, that were preinstalled.

It's inflexible - Once preloaded into a build, it's a permanent fixture of that build. If there are issues with the application - be that usability or security - it's going to be present every time a device running that build of Android is set up from a factory state. Obviously most applications will have a Google Play listing so the ability to update it after setup is a given, however until the OEM updates their build a new version of that application, and the OTA proliferates across their in-market devices, the risk remains.

It's inflexible (cont) - Partnerships end, and the money stops flowing. Whether being paid for a period of time, or based on activations, the application preloaded into the Android build is - as above - a permanent fixture of that build. It can be removed in an update, of course, but for the time it's there, that works against the OEM (but very much in favour of the app developer)

So how does PAI make this better?

What is PAI?

#PAI - Play Auto Install - is a partner service provided by Google that allows an OEM to configure applications recommended (or required) without preloading those applications in the Android build.

Rather, the OEM builds a simple system app with a default PAI configuration, and then uses the PAI (or Android Device Configuration) portal to provide the ongoing management of it.

Within the portal, the OEM can target:

- Region

- Carrier

- Build (Fingerprint)

- And by extension, OS version, custom builds for customers, etc.

- OEM key (a value OEMs can set within their builds for customisation purposes, try an

adb shell getprop | grep oem.keyon your Android device to see yours)

And more. There's a considerable amount of flexibility to allow for granular targeting, and new versions of configurations can be published in a few clicks that in turn deploy immediately to devices.

An example app config

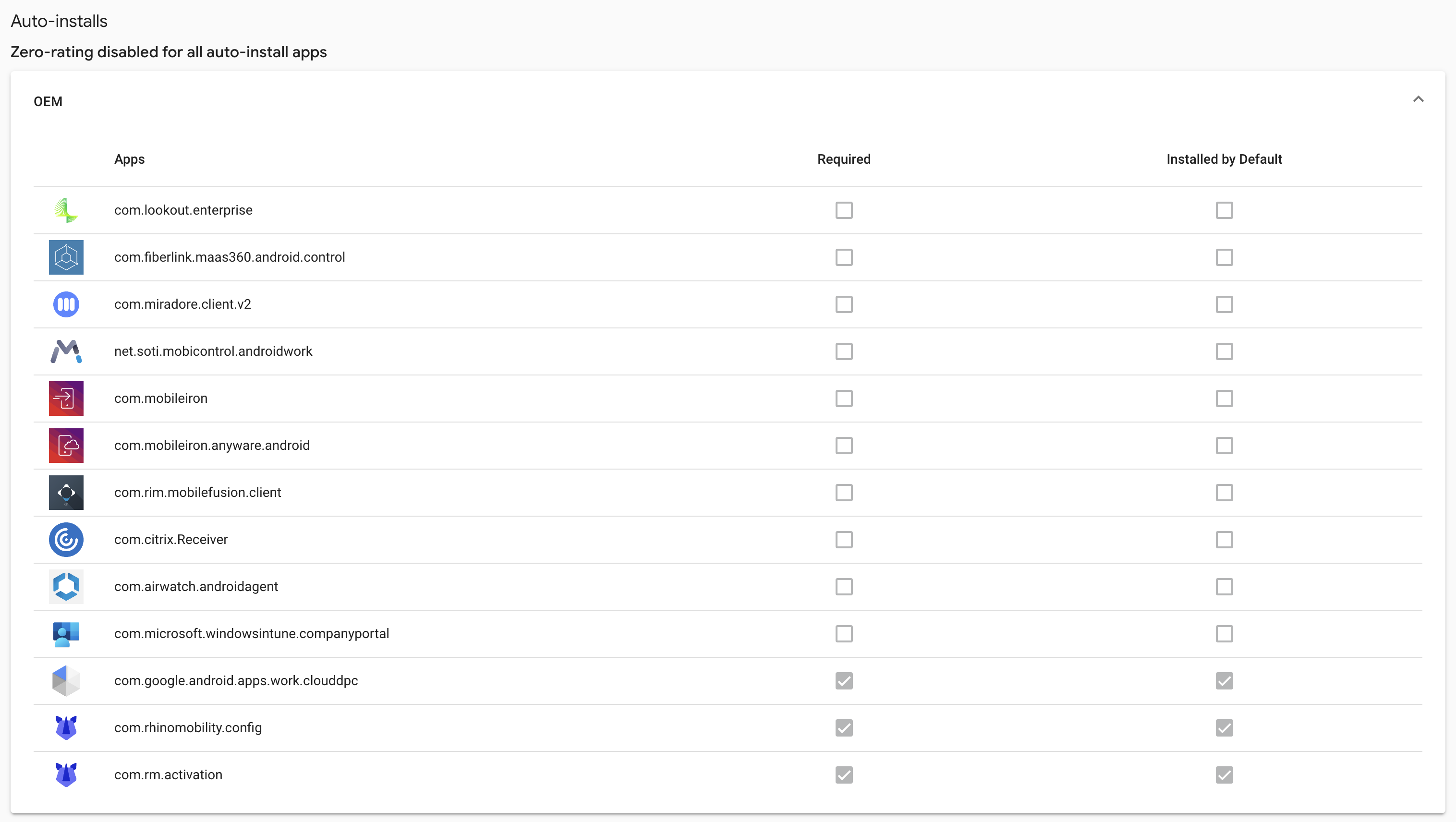

#Here's an example PAI application config. This below, incomplete example of a configuration follows a format similar to how I configured PAI with my products in the past, with the intention to offer applications to allow rapid enrolment without requiring a Google account (PAI allows for install without an account configured!), but allowing the user to skip the screen and install nothing if so desired.

Why offer this?

I was building devices with a primary use case for enterprise deployment. Although the likelihood was slim, my view was should a customer wish to use one of the tablets for both work and personal reasons, they could opt to set it up as a standard consumer device, and rapidly pull in the relevant DPC to enrol almost immediately without needing to head over to Google Play and locate the relevant agent themselves.

Did it get much use? I don't think so. But it was an opportunity to test PAI and so I gave it a go.

In the screenshot above you see Google, followed by Motorola. This order and layout is configured within the app (not shown below), along with the desired default applications to be offered as follows, in a file called default_layout.xml in most of the PAI apps I've torn down:

<?xml version="1.0" encoding="utf-8"?>

<workspace>

<autoinstall packageName="com.lookout.enterprise" className="com.lookout.enterprise.ui.android.activity.DispatchActivity" screen="2" x="0" y="4" groupid="0" requiredPreload="false" installByDefault="false" />

<autoinstall packageName="com.fiberlink.maas360.android.control" className="com.fiberlink.maas360.android.control.ui.SplashActivity" screen="2" x="1" y="4" groupid="0" requiredPreload="false" installByDefault="false" />

<autoinstall packageName="com.miradore.client.v2" className="com.miradore.client.ui.AuthenticationActivity" screen="2" x="2" y="4" groupid="0" requiredPreload="false" installByDefault="false" />

<autoinstall packageName="net.soti.mobicontrol.androidwork" className="net.soti.mobicontrol.startup.SplashActivity" screen="2" x="3" y="4" groupid="0" requiredPreload="false" installByDefault="false" />

<autoinstall packageName="com.mobileiron" className="com.mobileiron.MIClientMain" screen="2" x="4" y="4" groupid="0" requiredPreload="false" installByDefault="false" />

<autoinstall packageName="com.mobileiron.anyware.android" className="com.mobileiron.polaris.manager.ui.StartActivity" screen="2" x="5" y="4" groupid="0" requiredPreload="false" installByDefault="false" />

<autoinstall packageName="com.rim.mobilefusion.client" className="com.blackberry.ema.ui.HomeActivity" screen="2" x="1" y="3" groupid="0" requiredPreload="false" installByDefault="false" />

<autoinstall packageName="com.zenprise" className="com.citrix.work.common.activities.LauncherActivity" screen="2" x="2" y="3" groupid="0" requiredPreload="false" installByDefault="false" />

<autoinstall packageName="com.airwatch.androidagent" className="com.airwatch.agent.ui.activity.SplashActivity" screen="2" x="3" y="3" groupid="1" requiredPreload="false" installByDefault="false" />

<autoinstall packageName="com.microsoft.windowsintune.companyportal" className="com.microsoft.windowsintune.companyportal.views.SplashActivity" screen="2" x="4" y="3" groupid="1" requiredPreload="false" installByDefault="false" />

</workspace>

As you can see in the above, the two configs - beyond defining the apps themselves - are installByDefault and requiredPreload.

installByDefault is as it sounds, the application will be pulled down to the device automatically, and allows no user customisation.

requiredPreload if false allows the user to uncheck it, true marks it mandatory.

When this application is imported into the PAI Android Device Configuration portal, you end up with something that looks like this:

Above: An example of the type of PAI config I provided with devices

As an OEM, you don't technically have to define the applications in the app config, because once imported, the portal will allow full application selection and the ability to override the configuration either way. If you look closely above you'll notice there are no references to config or activation in the app config, they were instead added through the portal.

Additionally, with this config you can also define Google and Carrier apps accordingly.

How is it better?

#There are a few benefits to this approach

It can be adjusted at any time - Whether contracts for distribution end, a known issue is discovered, or any other reason an OEM may choose to cease deploying an application with their devices, it takes 5 minutes to edit and publish an updated PAI config, and no devices being set up from that moment will see the delisted application.

It's pushy, but not prohibitive - OEMs can mandate the installation of applications, but users retain the control to remove them if desired. Of course there are other means of preventing apps from being removed in the OS that can be leveraged with PAI, so if they wanted to, they could still choose to make users miserable.

There's no storage sacrifice - Predominantly a benefit for older OS versions, but all the same since apps are not being preloaded, they're not permanently taking up space within the build.

There's more flexibility - Apps can be offered without an install mandate. If developers want exposure, that's a reasonable, no-friction way of offering up your app without making the user feel like they need to take it.

It's simpler - You take all of the build-specific app-preload configuration and processes away from the OS developers, and handle it independently. If builds are being generated predominantly on preloaded applications (and if you know the dedicated world, you know that's not an unreasonable assumption), you can - in tandem with carrier and Runtime Resource Overlays handle a considerable amount of application and system customisation without needing to run multiple unique OS builds for it.

To conclude

#If you weren't aware of Play Auto Install before this, hopefully this offers some insight into what it is, any why you might see apps on your device with a name like PlayAutoInstalls. That said, OEMs can name them anything, so I wouldn't advocate checking for exactly that name in your system apps (but the package name is more likely to be consistent, following the convention of android.autoinstalls.config, have a look on your device with an ADB command like adb shell pm list packages | grep autoinstall)

It'll be a safe app to have there, but equally one safe to remove if you're rooted, as the StackExchange thread asks above.

Moreover, it's a better and more efficient way of handling app installs without preloading APKs into the Android build, and more OEMs should leverage it where preloading is otherwise in use.

Articles

2024

2023

- Mute @channel & @here notifications in Slack

- A guide to raising better support requests

- Ask Jason: How should we manage security and/or OS updates for our devices?

- Pixel 8 series launches with 7 years of software support

- Android's work profile behaviour has been reverted in 14 beta 5.3

- Fairphone raises the bar with commitment to Android updates

- Product files: The DoorDash T8

- Android's work profile gets a major upgrade in 14

- Google's inactive account policy may not impact Android Enterprise customers

- Product files: Alternative form factors and power solutions

- What's new in Android 14 for enterprise

- Introducing Micro Mobility

- Android Enterprise: A refresher

2022

- What I'd like to see from Android Enterprise in 2023

- Thoughts on Android 12's password complexity changes

- Google Play target API requirements & impact on enterprise applications

- Sunsetting Discuss comment platform

- Google publishes differences between Android and Android Go

- Android Go & EMM support

- Relaunching bayton.org

- AER dropped the 3/5 year update mandate with Android 11, where are we now?

- I made a bet with Google (and lost)

2020

- Product files: Building Android devices

- Google announce big changes to zero-touch

- VMware announces end of support for Device Admin

- Google launch the Android Enterprise Help Community

- Watch: An Android Enterprise discussion with Hypergate

- Listen again: BM podcast #144 - Jason Bayton & Russ Mohr talk Android!

- Google's Android Management API will soon support COPE

- Android Enterprise in 11: Google reduces visibility and control with COPE to bolster privacy.

- The decade that redefined Android in the enterprise

2019

- Why Intune doesn't support Android Enterprise COPE

- VMware WS1 UEM 1908 supports Android Enterprise enrolments on closed networks and AOSP devices

- The Bayton 2019 Android Enterprise experience survey

- Android Enterprise Partner Summit 2019 highlights

- The Huawei ban and Enterprise: what now?

- Dabbling with Android Enterprise in Q beta 3

- Why I moved from Google WiFi to Netgear Orbi

- I'm joining Social Mobile as Director of Android Innovation

- Android Enterprise in Q/10: features and clarity on DA deprecation

- MWC 2019: Mid-range devices excel, 5G everything, form-factors galore and Android Enterprise

- UEM tools managing Android-powered cars

- Joining the Android Enterprise Experts community

- February was an interesting month for OEMConfig

- Google launch Android Enterprise Recommended for Managed Service Providers

- Migrating from Windows 10 Mobile? Here's why you should consider Android

- AER expands: Android Enterprise Recommended for EMMs

- What I'd like to see from Android Enterprise in 2019

2018

- My top Android apps in 2018

- Year in review: 2018

- MobileIron Cloud R58 supports Android Enterprise fully managed devices with work profiles

- Hands on with the Huawei Mate 20 Pro

- Workspace ONE UEM 1810 introduces support for Android Enterprise fully managed devices with work profiles

- G Suite no longer prevents Android data leakage by default

- Live: Huawei Mate series launch

- How to sideload the Digital Wellbeing beta on Pie

- How to manually update the Nokia 7 Plus to Android Pie

- Hands on with the BQ Aquaris X2 Pro

- Hands on with Sony OEMConfig

- The state of Android Enterprise in 2018

- BYOD & Privacy: Don’t settle for legacy Android management in 2018

- Connecting two Synologies via SSH using public and private key authentication

- How to update Rsync on Mac OS Mojave and High Sierra

- Intune gains support for Android Enterprise COSU deployments

- Android Enterprise Recommended: HMD Global launch the Nokia 3.1 and Nokia 5.1

- Android Enterprise Partner Summit 2018 highlights

- Live: MobileIron LIVE! 2018

- Android Enterprise first: AirWatch 9.4 lands with a new name and focus

- Live: Android Enterprise Partner Summit 2018

- Samsung, Oreo and an inconsistent Android Enterprise UX

- MobileIron launch Android Enterprise work profiles on fully managed devices

- Android P demonstrates Google's focus on the enterprise

- An introduction to managed Google Play

- MWC 2018: Android One, Oreo Go, Android Enterprise Recommended & Android Enterprise

- Enterprise ready: Google launch Android Enterprise Recommended

2017

- Year in review: 2017

- Google is deprecating device admin in favour of Android Enterprise

- Hands on with the Sony Xperia XZ1 Compact

- Moto C Plus giveaway

- The state of Android Enterprise in 2017

- Samsung launched a Note 8 for enterprise

- MobileIron officially supports Android Enterprise QR code provisioning

- Android zero-touch enrolment has landed

- MobileIron unofficially supports QR provisioning for Android Enterprise work-managed devices, this is how I found it

- Hands on with the Nokia 3

- Experimenting with clustering and data replication in Nextcloud with MariaDB Galera and SyncThing

- Introducing documentation on bayton.org

- Goodbye Alexa, Hey Google: Hands on with the Google Home

- Restricting access to Exchange ActiveSync

- What is Mobile Device Management?

- 8 tips for a successful EMM deployment

- Long-term update: the fitlet-RM, a fanless industrial mini PC by Compulab

- First look: the FreedomPop V7

- Vault7 and the CIA: This is why we need EMM

- What is Android Enterprise (Android for Work) and why is it used?

- Introducing night mode on bayton.org

- What is iOS Supervision and why is it used?

- Hands on with the Galaxy TabPro S

- Introducing Nextcloud demo servers

- Part 4 - Project Obsidian: Obsidian is dead, long live Obsidian

2016

- My top Android apps 2016

- Hands on with the Linx 12V64

- Wandera review 2016: 2 years on

- Deploying MobileIron 9.1+ on KVM

- Hands on with the Nextcloud Box

- How a promoted tweet landed me on Finnish national news

- Using RWG Mobile for simple, cross-device centralised voicemail

- Part 3 – Project Obsidian: A change, data migration day 1 and build day 2

- Hands on: fitlet-RM, a fanless industrial mini PC by Compulab

- Part 2 - Project Obsidian: Build day 1

- Part 1 - Project Obsidian: Objectives & parts list

- Part 0 - Project Obsidian: Low power NAS & container server

- 5 Android apps improving my Chromebook experience

- First look: Android apps on ChromeOS

- Competition: Win 3 months of free VPS/Container hosting - Closed!

- ElasticHosts review

- ElasticHosts: Cloud Storage vs Folders, what's the difference?

- Adding bash completion to LXD

- Android N: First look & hands-on

- Springs.io - Container hosting at container prices

- Apple vs the FBI: This is why we need MDM

- Miradore Online MDM: Expanding management with subscriptions

- Lenovo Yoga 300 (11IBY) hard drive upgrade

- I bought a Lenovo Yoga 300, this is why I'm sending it back

- Restricting access to Exchange ActiveSync

- Switching to HTTPS on WordPress

2015

2014

- Is CYOD the answer to the BYOD headache?

- BYOD Management: Yes, we can wipe your phone

- A fortnight with Android Wear: LG G Watch review

- First look: Miradore Online free MDM

- Hands on: A weekend with Google Glass

- A month with Wandera Mobile Gateway

- Final thoughts: Dell Venue Pro 11 (Atom)

- Thoughts on BYOD

- Will 2014 bring better battery life?

- My year in review: Bayton.org

- The best purchase I've ever made? A Moto G for my father

2013

2012

- My Top Android Apps 12/12

- The Nexus 7 saga: Resolved

- Recycling Caps Lock into something useful - Ubuntu (12.04)

- The Nexus 7 saga continues

- From Wows to Woes: Why I won't be recommending a Nexus7 any time soon.

- Nexus7: What you need to know

- Why I disabled dlvr.it links on Facebook

- HTC Sense: Changing the lockscreen icons from within ADW

2011

- Push your Google+ posts to Twitter and Facebook

- Using multiple accounts with Google.

- The "Wn-R48" (Windows on the Cr-48)

- Want a Google+ invite?

- Publishing to external sources from Google+

- Dell Streak review. The Phone/Tablet Hybrid

- BlueInput: The Bluetooth HID driver Google forgot to include

- Pushing Buzz to Twitter with dlvr.it

- Managing your social outreach with dlvr.it

- When Awe met Some. The Cr-48 and Gnome3.

- Living with Google's Cr-48 and the cloud.

- Downtime 23-25/04/2011

- Are you practising "safe surfing"?

- The Virtualbox bug: "Cannot access the kernel driver" in Windows

- Putting tech into perspective

2010

- Have a Google Buzz Christmas

- Root a G1 running Android 1.6 without recovery!

- Windows 7 display issues on old Dell desktops

- Google added the Apps flexibility we've been waiting for!

- Part I: My 3 step program for moving to Google Apps

- Downloading torrents

- Completing the Buzz experience for Google Maps Mobile

- Quicktip: Trial Google Apps

- Quicktip: Save internet images fast

- Turn your desktop 3D!

- Part III - Device not compatible - Skype on 3

- Swype not compatible? ShapeWriter!

- Don't wait, get Swype now!

- HideIP VPN. Finally!

- Google enables Wave for Apps domains

- Aspire One touch screen

- Streamline XP into Ubuntu

- Edit a PDF with Zamzar

- Google offering Gmail addresses in the UK

- Google Wave: Revolutionising blogs!

- Hexxeh's Google Chrome OS builds

- Update: Buzz on Windows Mobile

- Alternatives to Internet Explorer

- Wordress 3.0 is coming!

- Skype for WM alternatives

- Browsing on a (data) budget? Opera!

- Buzz on unsupported mobiles

- Buzz on your desktop

- What's all the Buzz?

- Part II: Device not compatible - Skype on 3

- Part I - Device not compatible - Skype on 3

- Dreamscene on Windows 7

- Free Skype with 3? There's a catch..