Contents

Articles

2026

2025

- Google Play Protect is now the custom DPC gatekeeper, and everyone is a threat by default

- 12 deliveries of AE-mas (What shipped in Android Enterprise in 2025)

- The 12 AE requests of Christmas (2025 Edition)

- RCS Archival and you: clearing up the misconceptions

- Device Trust from Android Enterprise: What it is and how it works (hands-on)

- Android developer verification: what this means for consumers and enterprise

- AMAPI finally supports direct APK installation, this is how it works

- The Android Management API doesn't support pulling managed properties (config) from app tracks. Here's how to work around it

- Hands-on with CVE-2025-22442, a work profile sideloading vulnerability affecting most Android devices today

- AAB support for private apps in the managed Google Play iFrame is coming, take a first look here

- What's new (so far) for enterprise in Android 16

2024

- Android 15: What's new for enterprise?

- How Goto's acquisition of Miradore is eroding a once-promising MDM solution

- Google Play Protect no longer sends sideloaded applications for scanning on enterprise-managed devices

- Mobile Pros is moving to Discord

- Avoid another CrowdStrike takedown: Two approaches to replacing Windows

- Introducing MANAGED SETTINGS

- I'm joining NinjaOne

- Samsung announces Knox SDK restrictions for Android 15

- What's new (so far) for enterprise in Android 15

- Google quietly introduces new quotas for unvalidated AMAPI use

- What is Play Auto Install (PAI) in Android and how does it work?

- AMAPI publicly adds support for DPC migration

- How do Android devices become certified?

2023

- Mute @channel & @here notifications in Slack

- A guide to raising better support requests

- Ask Jason: How should we manage security and/or OS updates for our devices?

- Pixel 8 series launches with 7 years of software support

- Android's work profile behaviour has been reverted in 14 beta 5.3

- Fairphone raises the bar with commitment to Android updates

- Product files: The DoorDash T8

- Android's work profile gets a major upgrade in 14

- Google's inactive account policy may not impact Android Enterprise customers

- Product files: Alternative form factors and power solutions

- What's new in Android 14 for enterprise

- Introducing Micro Mobility

- Android Enterprise: A refresher

2022

- What I'd like to see from Android Enterprise in 2023

- Thoughts on Android 12's password complexity changes

- Google Play target API requirements & impact on enterprise applications

- Sunsetting Discuss comment platform

- Google publishes differences between Android and Android Go

- Android Go & EMM support

- Relaunching bayton.org

- AER dropped the 3/5 year update mandate with Android 11, where are we now?

- I made a bet with Google (and lost)

2020

- Product files: Building Android devices

- Google announce big changes to zero-touch

- VMware announces end of support for Device Admin

- Google launch the Android Enterprise Help Community

- Watch: An Android Enterprise discussion with Hypergate

- Listen again: BM podcast #144 - Jason Bayton & Russ Mohr talk Android!

- Google's Android Management API will soon support COPE

- Android Enterprise in 11: Google reduces visibility and control with COPE to bolster privacy.

- The decade that redefined Android in the enterprise

2019

- Why Intune doesn't support Android Enterprise COPE

- VMware WS1 UEM 1908 supports Android Enterprise enrolments on closed networks and AOSP devices

- The Bayton 2019 Android Enterprise experience survey

- Android Enterprise Partner Summit 2019 highlights

- The Huawei ban and Enterprise: what now?

- Dabbling with Android Enterprise in Q beta 3

- Why I moved from Google WiFi to Netgear Orbi

- I'm joining Social Mobile as Director of Android Innovation

- Android Enterprise in Q/10: features and clarity on DA deprecation

- MWC 2019: Mid-range devices excel, 5G everything, form-factors galore and Android Enterprise

- UEM tools managing Android-powered cars

- Joining the Android Enterprise Experts community

- February was an interesting month for OEMConfig

- Google launch Android Enterprise Recommended for Managed Service Providers

- Migrating from Windows 10 Mobile? Here's why you should consider Android

- AER expands: Android Enterprise Recommended for EMMs

- What I'd like to see from Android Enterprise in 2019

2018

- My top Android apps in 2018

- Year in review: 2018

- MobileIron Cloud R58 supports Android Enterprise fully managed devices with work profiles

- Hands on with the Huawei Mate 20 Pro

- Workspace ONE UEM 1810 introduces support for Android Enterprise fully managed devices with work profiles

- G Suite no longer prevents Android data leakage by default

- Live: Huawei Mate series launch

- How to sideload the Digital Wellbeing beta on Pie

- How to manually update the Nokia 7 Plus to Android Pie

- Hands on with the BQ Aquaris X2 Pro

- Hands on with Sony OEMConfig

- The state of Android Enterprise in 2018

- BYOD & Privacy: Don’t settle for legacy Android management in 2018

- Connecting two Synologies via SSH using public and private key authentication

- How to update Rsync on Mac OS Mojave and High Sierra

- Intune gains support for Android Enterprise COSU deployments

- Android Enterprise Recommended: HMD Global launch the Nokia 3.1 and Nokia 5.1

- Android Enterprise Partner Summit 2018 highlights

- Live: MobileIron LIVE! 2018

- Android Enterprise first: AirWatch 9.4 lands with a new name and focus

- Live: Android Enterprise Partner Summit 2018

- Samsung, Oreo and an inconsistent Android Enterprise UX

- MobileIron launch Android Enterprise work profiles on fully managed devices

- Android P demonstrates Google's focus on the enterprise

- An introduction to managed Google Play

- MWC 2018: Android One, Oreo Go, Android Enterprise Recommended & Android Enterprise

- Enterprise ready: Google launch Android Enterprise Recommended

2017

- Year in review: 2017

- Google is deprecating device admin in favour of Android Enterprise

- Hands on with the Sony Xperia XZ1 Compact

- Moto C Plus giveaway

- The state of Android Enterprise in 2017

- Samsung launched a Note 8 for enterprise

- MobileIron officially supports Android Enterprise QR code provisioning

- Android zero-touch enrolment has landed

- MobileIron unofficially supports QR provisioning for Android Enterprise work-managed devices, this is how I found it

- Hands on with the Nokia 3

- Experimenting with clustering and data replication in Nextcloud with MariaDB Galera and SyncThing

- Introducing documentation on bayton.org

- Goodbye Alexa, Hey Google: Hands on with the Google Home

- Restricting access to Exchange ActiveSync

- What is Mobile Device Management?

- 8 tips for a successful EMM deployment

- Long-term update: the fitlet-RM, a fanless industrial mini PC by Compulab

- First look: the FreedomPop V7

- Vault7 and the CIA: This is why we need EMM

- What is Android Enterprise (Android for Work) and why is it used?

- Introducing night mode on bayton.org

- What is iOS Supervision and why is it used?

- Hands on with the Galaxy TabPro S

- Introducing Nextcloud demo servers

- Part 4 - Project Obsidian: Obsidian is dead, long live Obsidian

2016

- My top Android apps 2016

- Hands on with the Linx 12V64

- Wandera review 2016: 2 years on

- Deploying MobileIron 9.1+ on KVM

- Hands on with the Nextcloud Box

- How a promoted tweet landed me on Finnish national news

- Using RWG Mobile for simple, cross-device centralised voicemail

- Part 3 – Project Obsidian: A change, data migration day 1 and build day 2

- Hands on: fitlet-RM, a fanless industrial mini PC by Compulab

- Part 2 - Project Obsidian: Build day 1

- Part 1 - Project Obsidian: Objectives & parts list

- Part 0 - Project Obsidian: Low power NAS & container server

- 5 Android apps improving my Chromebook experience

- First look: Android apps on ChromeOS

- Competition: Win 3 months of free VPS/Container hosting - Closed!

- ElasticHosts review

- ElasticHosts: Cloud Storage vs Folders, what's the difference?

- Adding bash completion to LXD

- Android N: First look & hands-on

- Springs.io - Container hosting at container prices

- Apple vs the FBI: This is why we need MDM

- Miradore Online MDM: Expanding management with subscriptions

- Lenovo Yoga 300 (11IBY) hard drive upgrade

- I bought a Lenovo Yoga 300, this is why I'm sending it back

- Restricting access to Exchange ActiveSync

- Switching to HTTPS on WordPress

2015

2014

- Is CYOD the answer to the BYOD headache?

- BYOD Management: Yes, we can wipe your phone

- A fortnight with Android Wear: LG G Watch review

- First look: Miradore Online free MDM

- Hands on: A weekend with Google Glass

- A month with Wandera Mobile Gateway

- Final thoughts: Dell Venue Pro 11 (Atom)

- Thoughts on BYOD

- Will 2014 bring better battery life?

- My year in review: Bayton.org

- The best purchase I've ever made? A Moto G for my father

2013

2012

- My Top Android Apps 12/12

- The Nexus 7 saga: Resolved

- Recycling Caps Lock into something useful - Ubuntu (12.04)

- The Nexus 7 saga continues

- From Wows to Woes: Why I won't be recommending a Nexus7 any time soon.

- Nexus7: What you need to know

- Why I disabled dlvr.it links on Facebook

- HTC Sense: Changing the lockscreen icons from within ADW

2011

- Push your Google+ posts to Twitter and Facebook

- Using multiple accounts with Google.

- The "Wn-R48" (Windows on the Cr-48)

- Want a Google+ invite?

- Publishing to external sources from Google+

- Dell Streak review. The Phone/Tablet Hybrid

- BlueInput: The Bluetooth HID driver Google forgot to include

- Pushing Buzz to Twitter with dlvr.it

- Managing your social outreach with dlvr.it

- When Awe met Some. The Cr-48 and Gnome3.

- Living with Google's Cr-48 and the cloud.

- Downtime 23-25/04/2011

- Are you practising "safe surfing"?

- The Virtualbox bug: "Cannot access the kernel driver" in Windows

- Putting tech into perspective

2010

- Have a Google Buzz Christmas

- Root a G1 running Android 1.6 without recovery!

- Windows 7 display issues on old Dell desktops

- Google added the Apps flexibility we've been waiting for!

- Part I: My 3 step program for moving to Google Apps

- Downloading torrents

- Completing the Buzz experience for Google Maps Mobile

- Quicktip: Trial Google Apps

- Quicktip: Save internet images fast

- Turn your desktop 3D!

- Part III - Device not compatible - Skype on 3

- Swype not compatible? ShapeWriter!

- Don't wait, get Swype now!

- HideIP VPN. Finally!

- Google enables Wave for Apps domains

- Aspire One touch screen

- Streamline XP into Ubuntu

- Edit a PDF with Zamzar

- Google offering Gmail addresses in the UK

- Google Wave: Revolutionising blogs!

- Hexxeh's Google Chrome OS builds

- Update: Buzz on Windows Mobile

- Alternatives to Internet Explorer

- Wordress 3.0 is coming!

- Skype for WM alternatives

- Browsing on a (data) budget? Opera!

- Buzz on unsupported mobiles

- Buzz on your desktop

- What's all the Buzz?

- Part II: Device not compatible - Skype on 3

- Part I - Device not compatible - Skype on 3

- Dreamscene on Windows 7

- Free Skype with 3? There's a catch..

Product files: Alternative form factors and power solutions

Contents

Welcome to Product Files, a series of articles that touch on some of the more interesting aspects of running a product organisation for the last several years.

As this series grows, additional links will show up here:

I last wrote about my job back in 2020. I think it's about time to change that, so in this article I'll cover off a hardware project, one of the first I took on when I joined my OEM way back in 2019 in fact, having not built devices before.

This project was also my first taste of what non-traditional Android form factors could look like, and was equally the first ePOS both for me and for the OEM having only recently pivoted from consumer low-cost handset projects to bespoke enterprise hardware.

In fact, this project ended up being a first for a few additional reasons -

- First device certified with Google's enterprise device licence agreement (EDLA) - more on this below.

- First (and one of few) partner hardware integrations, and associated SDK development

It goes without saying I've got a reasonably comprehensive understanding of Android. Though I focus primarily on enterprise, I've been tinkering with the platform for over a decade; the Android build that would ultimately grace the ePOS therefore wasn't much of a concern, but getting up to speed on hardware was to be an interesting challenge.

There were however two contributing factors that made this a little easier. First, I had an experienced team of hardware professionals both internally and through the ODM partners who would build the device. Second, the design and functionality of the ePOS was initially largely driven by a rather well-known customer in the food delivery industry based in the UK. If you happen to pop into a restaurant that partners with them, you'll no doubt see similarities in design with units they already have in the wild. When I took over the in-house device portfolio, that customer had just pulled out due to a change of priorities, and so I adopted the project to release as an open market device to sell globally.

And here it is:

I've got a soft spot for the M10p. Even though the design is dated and the way it's built could be far more efficient, thanks in part to the initial project scope, what eventually landed with customers was a robust, performant device with a solid suite of core hardware features, and wicked extensibility.

Some aspects of this project that made it stand out include:

Ports galore

#Customers purchasing ePOS devices often have peripherals from hardware being replaced. If they don't, they may prefer working with local partners for region or function specific peripheral hardware.

The goal for the M10p was to work with what customers want to work with. Could we have built scanners, cash registers, and payment terminals to bundle with the unit? Absolutely, but the strategy was that of compatibility and support, not lock-in.

When considering this, availability of ports was a priority.

Around the device you'll find 3 USB (A), USB-C, RJ11, RJ45, and RS232, amongst others. With them, the M10p acts as an all-in-one solution for payments, communications, and peripherals. It'll support many types of cash register, most external payment terminals, and with plenty of USB can be hooked into many other accessories as needed.

This wasn't simple to pull off, the MediaTek Genio 500 the unit is powered by - a strategic decision to further a close relationship with MTK's IoT division for long term support - is hardly a first choice for port support and a lot of these run from the USB2.0 and GPIO channels the SOC offers, but we made it work.

With all of those ports, though, this introduced another concern - keeping them clean and inconspicuous when not in use.

The original product design had them open to the elements, then a large all-or-nothing cover was added in.

(I appreciate it's not easy to see, zoom in on the picture, and you'll see the flap is open)

As you might imagine having one port in use requires the cover to be open, which again leaves all ports open to the elements.

I really aimed to achieve independent port access, and had a specific way I wanted them to function; rather than a simply spring-closed flap which can be fiddly and frustrating, I pushed for adding in a support that would hold the covers open when opened fully.

So we set out on a minor retooling of the housing to add supports for individual port covers, and ended up iterating a few times to get it right, but it was worth it for the resulting user experience.

The individual port covers use magnets to remain open against the metal housing of the print enclosure. It's a really nice, simple, considered implementation.

Continuing the trend of inconspicuous design, a lot of thought was also put in to avoiding unnecessary tampering. The M10p supports a full size SIM card and microSD (eSIM too, but that isn't user accessible either way). You wouldn't immediately know where these are looking at the unit, as they're hidden on the underside of the tablet behind an access port secured with a screw.

The same principle was applied for volume and the power button, which are recessed into the side of the unit and can only be interfaced with a SIM PIN (or equivalent). This was an intentional design decision as it's both inconvenient enough that the general populace won't have something to hand (like a Biro) to fiddle with it, while at the same time SIM PINs are cheap and reasonably standardised enough to allow for sourcing if customers lose the one in the box.

Custom APIs were also developed in software to allow for managing of device volume and tap-to-wake, so those buttons could be fully disabled under appropriate enterprise control, anyway.

The only concession made here was the inclusion of a USB-C port that handles host for Android debugging. I could have sunk my heels in on this, as ADB over Wi-Fi is obviously a viable option, but in testing and with the active customer base, debugging was challenging enough without introducing more complexity, and on reflection of 3 years supporting it, was the right move. Software handled access to this port also, of course.

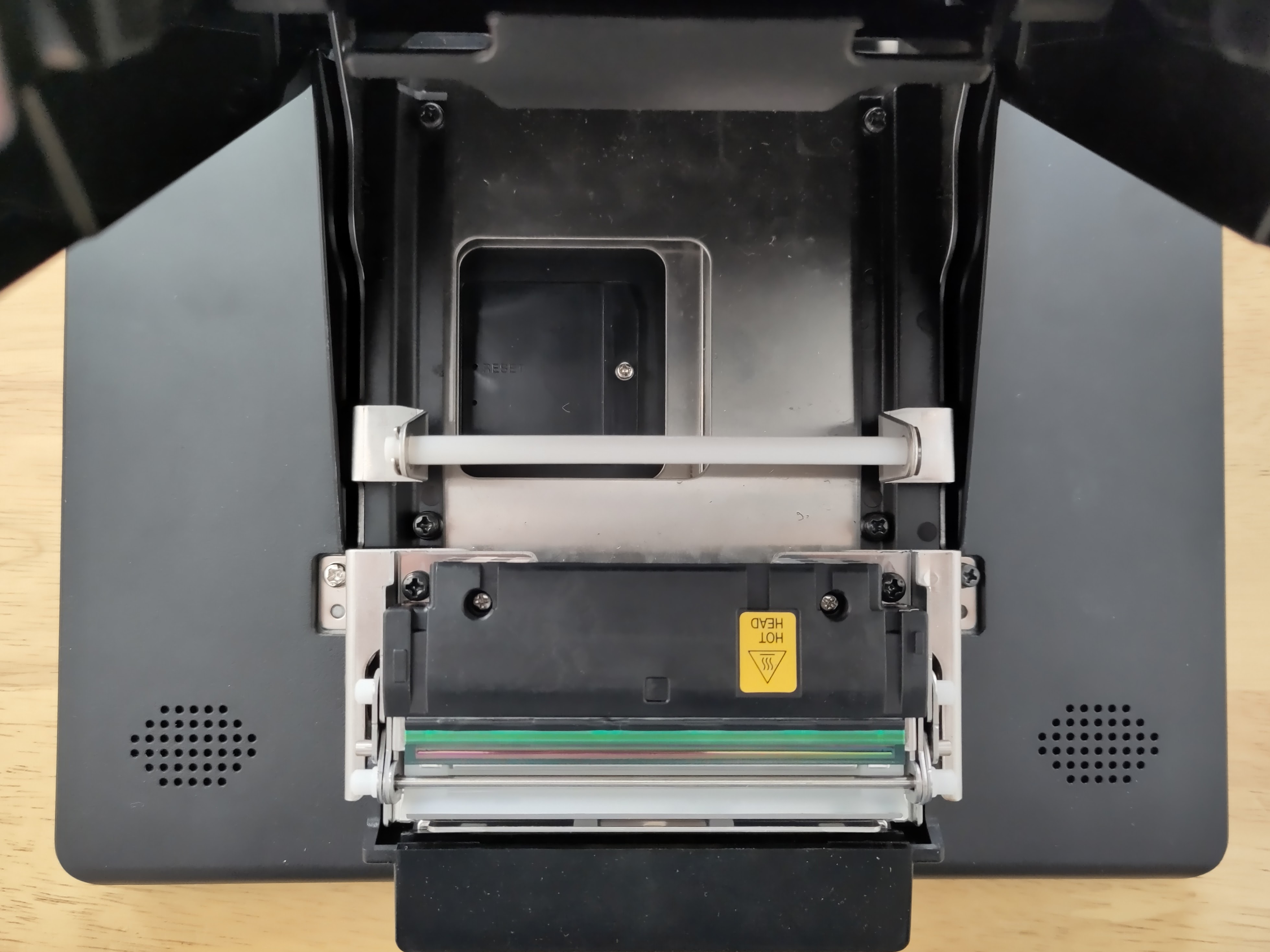

Despite the presence of USB-C, unfortunately I couldn't lean on it for power, particularly with a power-hungry Seiko sitting in the bottom. Today this would likely be reasonably easily achievable. In 2019 and due to the routing of power and data between the tablet and print enclosure respectfully, not so much. On the upside, the 24v external power supply has enough juice to power the tablet, print enclosure, peripherals, and many types of passively powered cash registers.

Safe shutdown on power loss

#Speaking of the external power supply, this is the sole means of powering the unit. There's no internal battery as it's a dedicated device designed to be fixed in place and attached to permanent power.

Considering the environments this device is intended to work within (high humidity, extremes of temperature, always on, running for 5+ years) shipping a battery is something I considered too high risk. Batteries fail, I didn't want this device to become a burden to customers, particularly in use cases such as food delivery, where units are remote, normally sat in partner establishments and going down can cost a day+ worth of missed orders.

There are implications to this product decision. First, with Google Play Protect (GMS) certification all certified devices must have a battery.

Further, in testing with customer environments, I was seeing unplanned power loss to be something of a reoccurring issue. Employees would often switch units off and on for app issues, devices would be turned off at the end of shift/work days, units would be moved around frequently(!), and other scenarios saw the M10p repeatedly shut down in an unclean fashion. This led to data loss and/or corruption and something I considered to be a significant problem.

Between the two, GMS was the larger - if ultimately temporary - issue for the business to be perfectly honest. Without certification the hardware couldn't run Google apps and services, and wouldn't support Android Enterprise. That would stifle the product's success tremendously.

My team and I worked through several options, including in-line UPS, hundreds-milliamp sized batteries accessible through maintenance panels for easy replacement, and more. Until it hit me.

Capacitors.

They hold charge, hold up in harsh environments, don't degrade in the way batteries do, and don't require user maintenance.

You see capacitors in use quite often today, consider things like the Samsung Galaxy stylus for example, but again back in 2019 it wasn't an immediate thought.

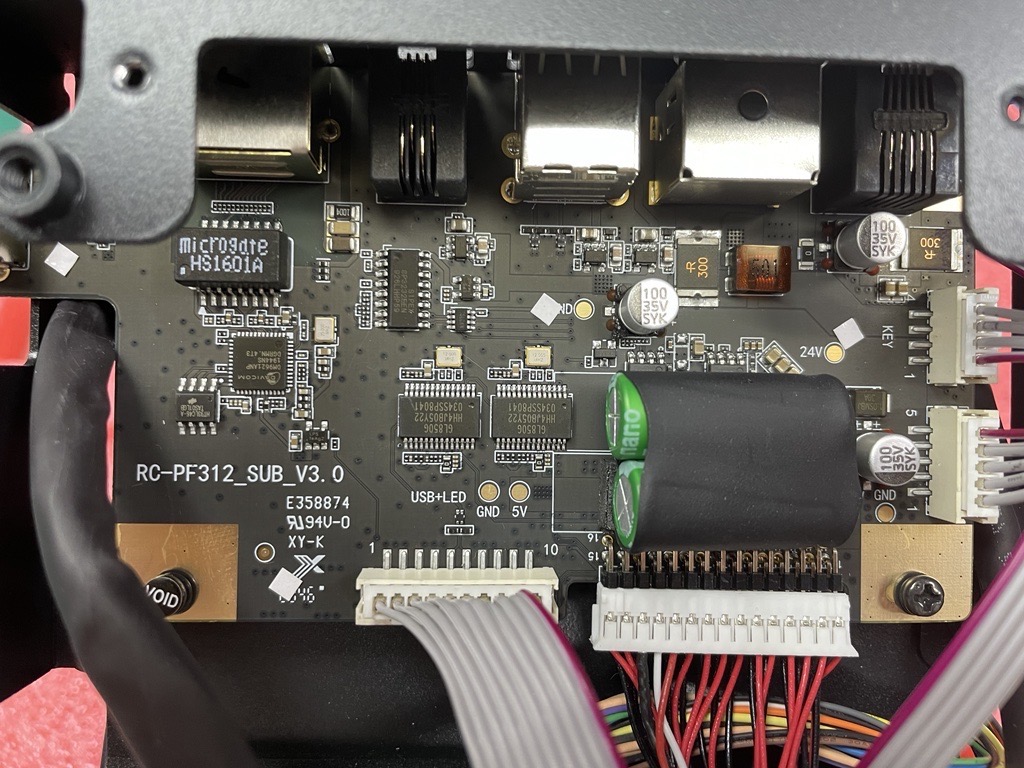

The M10p had the space within the housing needed to support them, and we sat them in-line between the PMIC - Power Management Integrated Circuit, the board that handles and distributes power to the rest of the device - and the external power supply.

We achieved 20 seconds of reserve power with the above configuration (the two large green cylinders wrapped in rubber), and while you might look at that insignificant number with confusion, this solved both problems:

- On a technicality we were able to pass GMS applying the MADA (consumer) contract with the unit classified as a portable tablet (for MADA it's that or a handset).

- The problem I set out to solve wasn't to keep the unit powered on with a loss of power, but to protect against data loss.

I coupled the capacitors with a system (Android) service that monitored for a power change, and gracefully initiated shutdown. With an average shutdown taking 16 seconds and including Android saving data to disk during the process, the M10p could now lose power without losing data.

I was elated.

Those familiar with capacitors may already know the minor trade-off we made with this configuration - cold boot takes 5-10s longer before the device powers on while the capacitors fill up. Cold boot only happens when the unit has been totally unplugged for a period of time though, giving the capacitors the opportunity to fully discharge over time. In temporary power loss scenarios this just wasn't an issue.

Migrating to EDLA

#That battery technicality for certifying the M10p as a Play Protect Certified/GMS MADA tablet ultimately (and thankfully) wasn't needed for production, as during development of the device Google launched EDLA, the Enterprise Device License Agreement, as a replacement for MADA, the Mobile Application Distribution Agreement.

What these are could probably justify an article per acronym, but effectively:

- All certified Android devices are governed by a MADA, for which there are multiple due to various competition and market restrictions around the world, EMADA (Europe), IMADA (India), TMADA (Turkey), and Russia which runs on a modified MADA.

- These agreements define apps bundled, home screen layout, restrictions and requirements in addition to or in place of the public CDD - Compatibility Definition Document - and more.

EDLA was brought in with some key requirements changes based on feedback from ecosystem players like me who outlined problems with the traditional GMS requirements for dedicated devices. In summary, again for simplicity, EDLA devices amongst other things:

- Can have displays larger than 18" (think kiosks, digital signage)

- Can be headless (no display at all)

- Can omit a battery entirely

The one primary requirement added was full transparency for software support, wherein a public page on the OEM website must state when the device is expected to go end-of-support, list releases, and so on. As you can imagine I had no issue with this at all. AER requirements demand the same and it's better for the ecosystem.

Evidently being invited to move the M10p over to EDLA from MADA was a big deal and put the device and it's capacitors back into the realm of absolute adherence as opposed to dancing around technicalities, so that was a relief, but to be invited to do so amongst the huge industry players like Zebra and co making dedicated devices was such an incredible accomplishment.

The M10p became the first EDLA-certified ePOS in the world, and I am super proud of that.

Wrap up

#I could go into much more detail on this device alone - the printer integration, the hinged access, BYO eSIM support, the light bar.. and more (and perhaps I will another time), but for this article these were some aspects of building the product that stood out, either due to time and thought required, or the impact it had on the resulting device.

I hope you enjoyed this peek behind the curtains. If so, look out for more in the coming months!

Articles

2026

2025

- Google Play Protect is now the custom DPC gatekeeper, and everyone is a threat by default

- 12 deliveries of AE-mas (What shipped in Android Enterprise in 2025)

- The 12 AE requests of Christmas (2025 Edition)

- RCS Archival and you: clearing up the misconceptions

- Device Trust from Android Enterprise: What it is and how it works (hands-on)

- Android developer verification: what this means for consumers and enterprise

- AMAPI finally supports direct APK installation, this is how it works

- The Android Management API doesn't support pulling managed properties (config) from app tracks. Here's how to work around it

- Hands-on with CVE-2025-22442, a work profile sideloading vulnerability affecting most Android devices today

- AAB support for private apps in the managed Google Play iFrame is coming, take a first look here

- What's new (so far) for enterprise in Android 16

2024

- Android 15: What's new for enterprise?

- How Goto's acquisition of Miradore is eroding a once-promising MDM solution

- Google Play Protect no longer sends sideloaded applications for scanning on enterprise-managed devices

- Mobile Pros is moving to Discord

- Avoid another CrowdStrike takedown: Two approaches to replacing Windows

- Introducing MANAGED SETTINGS

- I'm joining NinjaOne

- Samsung announces Knox SDK restrictions for Android 15

- What's new (so far) for enterprise in Android 15

- Google quietly introduces new quotas for unvalidated AMAPI use

- What is Play Auto Install (PAI) in Android and how does it work?

- AMAPI publicly adds support for DPC migration

- How do Android devices become certified?

2023

- Mute @channel & @here notifications in Slack

- A guide to raising better support requests

- Ask Jason: How should we manage security and/or OS updates for our devices?

- Pixel 8 series launches with 7 years of software support

- Android's work profile behaviour has been reverted in 14 beta 5.3

- Fairphone raises the bar with commitment to Android updates

- Product files: The DoorDash T8

- Android's work profile gets a major upgrade in 14

- Google's inactive account policy may not impact Android Enterprise customers

- Product files: Alternative form factors and power solutions

- What's new in Android 14 for enterprise

- Introducing Micro Mobility

- Android Enterprise: A refresher

2022

- What I'd like to see from Android Enterprise in 2023

- Thoughts on Android 12's password complexity changes

- Google Play target API requirements & impact on enterprise applications

- Sunsetting Discuss comment platform

- Google publishes differences between Android and Android Go

- Android Go & EMM support

- Relaunching bayton.org

- AER dropped the 3/5 year update mandate with Android 11, where are we now?

- I made a bet with Google (and lost)

2020

- Product files: Building Android devices

- Google announce big changes to zero-touch

- VMware announces end of support for Device Admin

- Google launch the Android Enterprise Help Community

- Watch: An Android Enterprise discussion with Hypergate

- Listen again: BM podcast #144 - Jason Bayton & Russ Mohr talk Android!

- Google's Android Management API will soon support COPE

- Android Enterprise in 11: Google reduces visibility and control with COPE to bolster privacy.

- The decade that redefined Android in the enterprise

2019

- Why Intune doesn't support Android Enterprise COPE

- VMware WS1 UEM 1908 supports Android Enterprise enrolments on closed networks and AOSP devices

- The Bayton 2019 Android Enterprise experience survey

- Android Enterprise Partner Summit 2019 highlights

- The Huawei ban and Enterprise: what now?

- Dabbling with Android Enterprise in Q beta 3

- Why I moved from Google WiFi to Netgear Orbi

- I'm joining Social Mobile as Director of Android Innovation

- Android Enterprise in Q/10: features and clarity on DA deprecation

- MWC 2019: Mid-range devices excel, 5G everything, form-factors galore and Android Enterprise

- UEM tools managing Android-powered cars

- Joining the Android Enterprise Experts community

- February was an interesting month for OEMConfig

- Google launch Android Enterprise Recommended for Managed Service Providers

- Migrating from Windows 10 Mobile? Here's why you should consider Android

- AER expands: Android Enterprise Recommended for EMMs

- What I'd like to see from Android Enterprise in 2019

2018

- My top Android apps in 2018

- Year in review: 2018

- MobileIron Cloud R58 supports Android Enterprise fully managed devices with work profiles

- Hands on with the Huawei Mate 20 Pro

- Workspace ONE UEM 1810 introduces support for Android Enterprise fully managed devices with work profiles

- G Suite no longer prevents Android data leakage by default

- Live: Huawei Mate series launch

- How to sideload the Digital Wellbeing beta on Pie

- How to manually update the Nokia 7 Plus to Android Pie

- Hands on with the BQ Aquaris X2 Pro

- Hands on with Sony OEMConfig

- The state of Android Enterprise in 2018

- BYOD & Privacy: Don’t settle for legacy Android management in 2018

- Connecting two Synologies via SSH using public and private key authentication

- How to update Rsync on Mac OS Mojave and High Sierra

- Intune gains support for Android Enterprise COSU deployments

- Android Enterprise Recommended: HMD Global launch the Nokia 3.1 and Nokia 5.1

- Android Enterprise Partner Summit 2018 highlights

- Live: MobileIron LIVE! 2018

- Android Enterprise first: AirWatch 9.4 lands with a new name and focus

- Live: Android Enterprise Partner Summit 2018

- Samsung, Oreo and an inconsistent Android Enterprise UX

- MobileIron launch Android Enterprise work profiles on fully managed devices

- Android P demonstrates Google's focus on the enterprise

- An introduction to managed Google Play

- MWC 2018: Android One, Oreo Go, Android Enterprise Recommended & Android Enterprise

- Enterprise ready: Google launch Android Enterprise Recommended

2017

- Year in review: 2017

- Google is deprecating device admin in favour of Android Enterprise

- Hands on with the Sony Xperia XZ1 Compact

- Moto C Plus giveaway

- The state of Android Enterprise in 2017

- Samsung launched a Note 8 for enterprise

- MobileIron officially supports Android Enterprise QR code provisioning

- Android zero-touch enrolment has landed

- MobileIron unofficially supports QR provisioning for Android Enterprise work-managed devices, this is how I found it

- Hands on with the Nokia 3

- Experimenting with clustering and data replication in Nextcloud with MariaDB Galera and SyncThing

- Introducing documentation on bayton.org

- Goodbye Alexa, Hey Google: Hands on with the Google Home

- Restricting access to Exchange ActiveSync

- What is Mobile Device Management?

- 8 tips for a successful EMM deployment

- Long-term update: the fitlet-RM, a fanless industrial mini PC by Compulab

- First look: the FreedomPop V7

- Vault7 and the CIA: This is why we need EMM

- What is Android Enterprise (Android for Work) and why is it used?

- Introducing night mode on bayton.org

- What is iOS Supervision and why is it used?

- Hands on with the Galaxy TabPro S

- Introducing Nextcloud demo servers

- Part 4 - Project Obsidian: Obsidian is dead, long live Obsidian

2016

- My top Android apps 2016

- Hands on with the Linx 12V64

- Wandera review 2016: 2 years on

- Deploying MobileIron 9.1+ on KVM

- Hands on with the Nextcloud Box

- How a promoted tweet landed me on Finnish national news

- Using RWG Mobile for simple, cross-device centralised voicemail

- Part 3 – Project Obsidian: A change, data migration day 1 and build day 2

- Hands on: fitlet-RM, a fanless industrial mini PC by Compulab

- Part 2 - Project Obsidian: Build day 1

- Part 1 - Project Obsidian: Objectives & parts list

- Part 0 - Project Obsidian: Low power NAS & container server

- 5 Android apps improving my Chromebook experience

- First look: Android apps on ChromeOS

- Competition: Win 3 months of free VPS/Container hosting - Closed!

- ElasticHosts review

- ElasticHosts: Cloud Storage vs Folders, what's the difference?

- Adding bash completion to LXD

- Android N: First look & hands-on

- Springs.io - Container hosting at container prices

- Apple vs the FBI: This is why we need MDM

- Miradore Online MDM: Expanding management with subscriptions

- Lenovo Yoga 300 (11IBY) hard drive upgrade

- I bought a Lenovo Yoga 300, this is why I'm sending it back

- Restricting access to Exchange ActiveSync

- Switching to HTTPS on WordPress

2015

2014

- Is CYOD the answer to the BYOD headache?

- BYOD Management: Yes, we can wipe your phone

- A fortnight with Android Wear: LG G Watch review

- First look: Miradore Online free MDM

- Hands on: A weekend with Google Glass

- A month with Wandera Mobile Gateway

- Final thoughts: Dell Venue Pro 11 (Atom)

- Thoughts on BYOD

- Will 2014 bring better battery life?

- My year in review: Bayton.org

- The best purchase I've ever made? A Moto G for my father

2013

2012

- My Top Android Apps 12/12

- The Nexus 7 saga: Resolved

- Recycling Caps Lock into something useful - Ubuntu (12.04)

- The Nexus 7 saga continues

- From Wows to Woes: Why I won't be recommending a Nexus7 any time soon.

- Nexus7: What you need to know

- Why I disabled dlvr.it links on Facebook

- HTC Sense: Changing the lockscreen icons from within ADW

2011

- Push your Google+ posts to Twitter and Facebook

- Using multiple accounts with Google.

- The "Wn-R48" (Windows on the Cr-48)

- Want a Google+ invite?

- Publishing to external sources from Google+

- Dell Streak review. The Phone/Tablet Hybrid

- BlueInput: The Bluetooth HID driver Google forgot to include

- Pushing Buzz to Twitter with dlvr.it

- Managing your social outreach with dlvr.it

- When Awe met Some. The Cr-48 and Gnome3.

- Living with Google's Cr-48 and the cloud.

- Downtime 23-25/04/2011

- Are you practising "safe surfing"?

- The Virtualbox bug: "Cannot access the kernel driver" in Windows

- Putting tech into perspective

2010

- Have a Google Buzz Christmas

- Root a G1 running Android 1.6 without recovery!

- Windows 7 display issues on old Dell desktops

- Google added the Apps flexibility we've been waiting for!

- Part I: My 3 step program for moving to Google Apps

- Downloading torrents

- Completing the Buzz experience for Google Maps Mobile

- Quicktip: Trial Google Apps

- Quicktip: Save internet images fast

- Turn your desktop 3D!

- Part III - Device not compatible - Skype on 3

- Swype not compatible? ShapeWriter!

- Don't wait, get Swype now!

- HideIP VPN. Finally!

- Google enables Wave for Apps domains

- Aspire One touch screen

- Streamline XP into Ubuntu

- Edit a PDF with Zamzar

- Google offering Gmail addresses in the UK

- Google Wave: Revolutionising blogs!

- Hexxeh's Google Chrome OS builds

- Update: Buzz on Windows Mobile

- Alternatives to Internet Explorer

- Wordress 3.0 is coming!

- Skype for WM alternatives

- Browsing on a (data) budget? Opera!

- Buzz on unsupported mobiles

- Buzz on your desktop

- What's all the Buzz?

- Part II: Device not compatible - Skype on 3

- Part I - Device not compatible - Skype on 3

- Dreamscene on Windows 7

- Free Skype with 3? There's a catch..