Contents

Articles

2026

2025

- Google Play Protect is now the custom DPC gatekeeper, and everyone is a threat by default

- 12 deliveries of AE-mas (What shipped in Android Enterprise in 2025)

- The 12 AE requests of Christmas (2025 Edition)

- RCS Archival and you: clearing up the misconceptions

- Device Trust from Android Enterprise: What it is and how it works (hands-on)

- Android developer verification: what this means for consumers and enterprise

- AMAPI finally supports direct APK installation, this is how it works

- The Android Management API doesn't support pulling managed properties (config) from app tracks. Here's how to work around it

- Hands-on with CVE-2025-22442, a work profile sideloading vulnerability affecting most Android devices today

- AAB support for private apps in the managed Google Play iFrame is coming, take a first look here

- What's new (so far) for enterprise in Android 16

2024

- Android 15: What's new for enterprise?

- How Goto's acquisition of Miradore is eroding a once-promising MDM solution

- Google Play Protect no longer sends sideloaded applications for scanning on enterprise-managed devices

- Mobile Pros is moving to Discord

- Avoid another CrowdStrike takedown: Two approaches to replacing Windows

- Introducing MANAGED SETTINGS

- I'm joining NinjaOne

- Samsung announces Knox SDK restrictions for Android 15

- What's new (so far) for enterprise in Android 15

- Google quietly introduces new quotas for unvalidated AMAPI use

- What is Play Auto Install (PAI) in Android and how does it work?

- AMAPI publicly adds support for DPC migration

- How do Android devices become certified?

2023

- Mute @channel & @here notifications in Slack

- A guide to raising better support requests

- Ask Jason: How should we manage security and/or OS updates for our devices?

- Pixel 8 series launches with 7 years of software support

- Android's work profile behaviour has been reverted in 14 beta 5.3

- Fairphone raises the bar with commitment to Android updates

- Product files: The DoorDash T8

- Android's work profile gets a major upgrade in 14

- Google's inactive account policy may not impact Android Enterprise customers

- Product files: Alternative form factors and power solutions

- What's new in Android 14 for enterprise

- Introducing Micro Mobility

- Android Enterprise: A refresher

2022

- What I'd like to see from Android Enterprise in 2023

- Thoughts on Android 12's password complexity changes

- Google Play target API requirements & impact on enterprise applications

- Sunsetting Discuss comment platform

- Google publishes differences between Android and Android Go

- Android Go & EMM support

- Relaunching bayton.org

- AER dropped the 3/5 year update mandate with Android 11, where are we now?

- I made a bet with Google (and lost)

2020

- Product files: Building Android devices

- Google announce big changes to zero-touch

- VMware announces end of support for Device Admin

- Google launch the Android Enterprise Help Community

- Watch: An Android Enterprise discussion with Hypergate

- Listen again: BM podcast #144 - Jason Bayton & Russ Mohr talk Android!

- Google's Android Management API will soon support COPE

- Android Enterprise in 11: Google reduces visibility and control with COPE to bolster privacy.

- The decade that redefined Android in the enterprise

2019

- Why Intune doesn't support Android Enterprise COPE

- VMware WS1 UEM 1908 supports Android Enterprise enrolments on closed networks and AOSP devices

- The Bayton 2019 Android Enterprise experience survey

- Android Enterprise Partner Summit 2019 highlights

- The Huawei ban and Enterprise: what now?

- Dabbling with Android Enterprise in Q beta 3

- Why I moved from Google WiFi to Netgear Orbi

- I'm joining Social Mobile as Director of Android Innovation

- Android Enterprise in Q/10: features and clarity on DA deprecation

- MWC 2019: Mid-range devices excel, 5G everything, form-factors galore and Android Enterprise

- UEM tools managing Android-powered cars

- Joining the Android Enterprise Experts community

- February was an interesting month for OEMConfig

- Google launch Android Enterprise Recommended for Managed Service Providers

- Migrating from Windows 10 Mobile? Here's why you should consider Android

- AER expands: Android Enterprise Recommended for EMMs

- What I'd like to see from Android Enterprise in 2019

2018

- My top Android apps in 2018

- Year in review: 2018

- MobileIron Cloud R58 supports Android Enterprise fully managed devices with work profiles

- Hands on with the Huawei Mate 20 Pro

- Workspace ONE UEM 1810 introduces support for Android Enterprise fully managed devices with work profiles

- G Suite no longer prevents Android data leakage by default

- Live: Huawei Mate series launch

- How to sideload the Digital Wellbeing beta on Pie

- How to manually update the Nokia 7 Plus to Android Pie

- Hands on with the BQ Aquaris X2 Pro

- Hands on with Sony OEMConfig

- The state of Android Enterprise in 2018

- BYOD & Privacy: Don’t settle for legacy Android management in 2018

- Connecting two Synologies via SSH using public and private key authentication

- How to update Rsync on Mac OS Mojave and High Sierra

- Intune gains support for Android Enterprise COSU deployments

- Android Enterprise Recommended: HMD Global launch the Nokia 3.1 and Nokia 5.1

- Android Enterprise Partner Summit 2018 highlights

- Live: MobileIron LIVE! 2018

- Android Enterprise first: AirWatch 9.4 lands with a new name and focus

- Live: Android Enterprise Partner Summit 2018

- Samsung, Oreo and an inconsistent Android Enterprise UX

- MobileIron launch Android Enterprise work profiles on fully managed devices

- Android P demonstrates Google's focus on the enterprise

- An introduction to managed Google Play

- MWC 2018: Android One, Oreo Go, Android Enterprise Recommended & Android Enterprise

- Enterprise ready: Google launch Android Enterprise Recommended

2017

- Year in review: 2017

- Google is deprecating device admin in favour of Android Enterprise

- Hands on with the Sony Xperia XZ1 Compact

- Moto C Plus giveaway

- The state of Android Enterprise in 2017

- Samsung launched a Note 8 for enterprise

- MobileIron officially supports Android Enterprise QR code provisioning

- Android zero-touch enrolment has landed

- MobileIron unofficially supports QR provisioning for Android Enterprise work-managed devices, this is how I found it

- Hands on with the Nokia 3

- Experimenting with clustering and data replication in Nextcloud with MariaDB Galera and SyncThing

- Introducing documentation on bayton.org

- Goodbye Alexa, Hey Google: Hands on with the Google Home

- Restricting access to Exchange ActiveSync

- What is Mobile Device Management?

- 8 tips for a successful EMM deployment

- Long-term update: the fitlet-RM, a fanless industrial mini PC by Compulab

- First look: the FreedomPop V7

- Vault7 and the CIA: This is why we need EMM

- What is Android Enterprise (Android for Work) and why is it used?

- Introducing night mode on bayton.org

- What is iOS Supervision and why is it used?

- Hands on with the Galaxy TabPro S

- Introducing Nextcloud demo servers

- Part 4 - Project Obsidian: Obsidian is dead, long live Obsidian

2016

- My top Android apps 2016

- Hands on with the Linx 12V64

- Wandera review 2016: 2 years on

- Deploying MobileIron 9.1+ on KVM

- Hands on with the Nextcloud Box

- How a promoted tweet landed me on Finnish national news

- Using RWG Mobile for simple, cross-device centralised voicemail

- Part 3 – Project Obsidian: A change, data migration day 1 and build day 2

- Hands on: fitlet-RM, a fanless industrial mini PC by Compulab

- Part 2 - Project Obsidian: Build day 1

- Part 1 - Project Obsidian: Objectives & parts list

- Part 0 - Project Obsidian: Low power NAS & container server

- 5 Android apps improving my Chromebook experience

- First look: Android apps on ChromeOS

- Competition: Win 3 months of free VPS/Container hosting - Closed!

- ElasticHosts review

- ElasticHosts: Cloud Storage vs Folders, what's the difference?

- Adding bash completion to LXD

- Android N: First look & hands-on

- Springs.io - Container hosting at container prices

- Apple vs the FBI: This is why we need MDM

- Miradore Online MDM: Expanding management with subscriptions

- Lenovo Yoga 300 (11IBY) hard drive upgrade

- I bought a Lenovo Yoga 300, this is why I'm sending it back

- Restricting access to Exchange ActiveSync

- Switching to HTTPS on WordPress

2015

2014

- Is CYOD the answer to the BYOD headache?

- BYOD Management: Yes, we can wipe your phone

- A fortnight with Android Wear: LG G Watch review

- First look: Miradore Online free MDM

- Hands on: A weekend with Google Glass

- A month with Wandera Mobile Gateway

- Final thoughts: Dell Venue Pro 11 (Atom)

- Thoughts on BYOD

- Will 2014 bring better battery life?

- My year in review: Bayton.org

- The best purchase I've ever made? A Moto G for my father

2013

2012

- My Top Android Apps 12/12

- The Nexus 7 saga: Resolved

- Recycling Caps Lock into something useful - Ubuntu (12.04)

- The Nexus 7 saga continues

- From Wows to Woes: Why I won't be recommending a Nexus7 any time soon.

- Nexus7: What you need to know

- Why I disabled dlvr.it links on Facebook

- HTC Sense: Changing the lockscreen icons from within ADW

2011

- Push your Google+ posts to Twitter and Facebook

- Using multiple accounts with Google.

- The "Wn-R48" (Windows on the Cr-48)

- Want a Google+ invite?

- Publishing to external sources from Google+

- Dell Streak review. The Phone/Tablet Hybrid

- BlueInput: The Bluetooth HID driver Google forgot to include

- Pushing Buzz to Twitter with dlvr.it

- Managing your social outreach with dlvr.it

- When Awe met Some. The Cr-48 and Gnome3.

- Living with Google's Cr-48 and the cloud.

- Downtime 23-25/04/2011

- Are you practising "safe surfing"?

- The Virtualbox bug: "Cannot access the kernel driver" in Windows

- Putting tech into perspective

2010

- Have a Google Buzz Christmas

- Root a G1 running Android 1.6 without recovery!

- Windows 7 display issues on old Dell desktops

- Google added the Apps flexibility we've been waiting for!

- Part I: My 3 step program for moving to Google Apps

- Downloading torrents

- Completing the Buzz experience for Google Maps Mobile

- Quicktip: Trial Google Apps

- Quicktip: Save internet images fast

- Turn your desktop 3D!

- Part III - Device not compatible - Skype on 3

- Swype not compatible? ShapeWriter!

- Don't wait, get Swype now!

- HideIP VPN. Finally!

- Google enables Wave for Apps domains

- Aspire One touch screen

- Streamline XP into Ubuntu

- Edit a PDF with Zamzar

- Google offering Gmail addresses in the UK

- Google Wave: Revolutionising blogs!

- Hexxeh's Google Chrome OS builds

- Update: Buzz on Windows Mobile

- Alternatives to Internet Explorer

- Wordress 3.0 is coming!

- Skype for WM alternatives

- Browsing on a (data) budget? Opera!

- Buzz on unsupported mobiles

- Buzz on your desktop

- What's all the Buzz?

- Part II: Device not compatible - Skype on 3

- Part I - Device not compatible - Skype on 3

- Dreamscene on Windows 7

- Free Skype with 3? There's a catch..

Change log

The decade that redefined Android in the enterprise

Contents

2019 and, indeed, the decade has now drawn to a close; as the 20’s have now roared in, what better time to take a look back at how the 10’s saw the most popular mobile OS in today’s world evolve from being mostly unsuitable for enterprise to an obvious choice?

From the days of Device Admin management, manually provisioning devices, dealing with Google accounts, devices that weren’t guaranteed to offer any more than basic Exchange account support (which in itself was a stretch for some), the inconsistent management experiences between EMM solutions, and everything else the admins, consultants and engineers of the EMM world have put up with over the years, to OEMs like Samsung and Zebra taking matters into their own hands to offer solutions for enterprise, and Google eventually turning their focus to enterprise and security with what would become Android Enterprise.

It’s been a pretty fascinating decade.

With that, here’s a look back across the last 10 years bundled with a smidge of my experiences as well as thoughts from a few friends in the ecosystem thrown in for good measure! I’ll preface this with a heads up that I’ve covered a lot of these topics in detail over on /Android, so those who’ve followed my content before may see some familiar themes.

Way back when

#Android and Windows Mobile

#Back when I first started out I was used to seeing Windows Mobile devices widely used in enterprise. From logistics to field forces, knowledge workers to dedicated. Windows Mobile was everywhere.

Honestly, if Microsoft hadn’t ruined everything with Windows Phone and instead maintained focus on iterating with Windows Mobile, the landscape today might be different. I was an avid Windows Mobile user, from 5 to 6.5 regularly and later alongside Android, before fully abandoning the platform once Windows Phone came along (I do however still have a Lumia in one of my drawers for testing Continuum when that was a thing).

The mistakes Microsoft ultimately made gave Android a huge leg up on the market to provide a drop-in alternative (literally in some cases. Anyone remember the HTC HD2? That thing ran everything. Even my HTC TyTN II ended up upgrading to Android after spending enough time with Android to deem it a worthy change) and I’ve watched with interest as rugged and dedicated OEMs slowly moved away from Windows to embrace Android with open arms.

It’s no surprise given Android was originally targeting the Windows Mobile market. It was just as well they rapidly pivoted to instead more directly compete with iOS (more touch, fewer buttons) as it certainly wouldn’t be the OS it is today without a bit of modern competition.

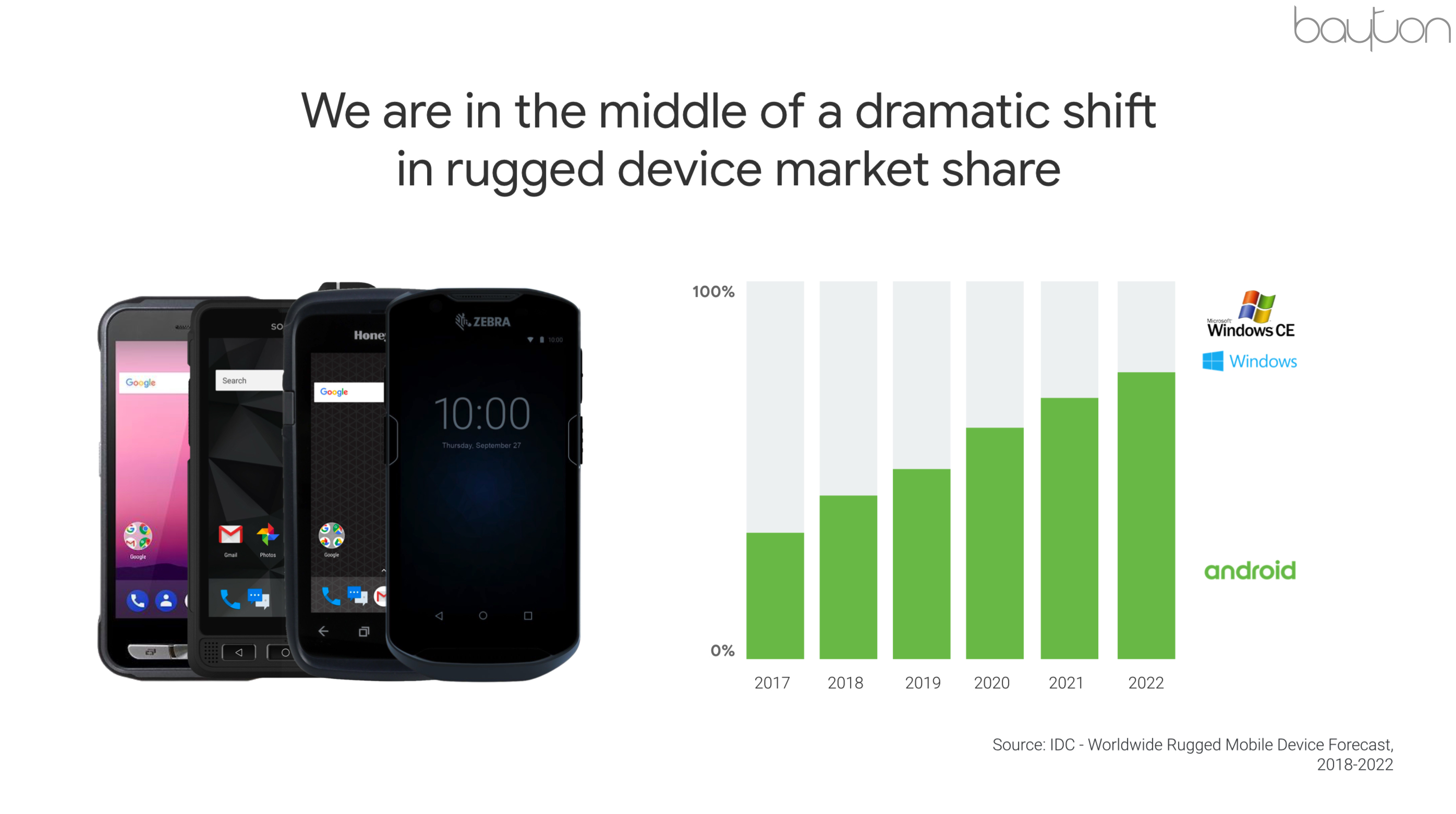

Windows is still in use in organisations today, not necessarily Windows Mobile so much as CE and modern versions of the OS; Microsoft has by no means been eradicated, but it’s share of the enterprise space is being slowly and reliably eroded, as Google pointed out at the Summit:

Samsung or no one

#Before Android Enterprise, managing devices typically for most organisations meant buying and supporting Samsung, and only Samsung. Of course OEMs like Zebra in the more specialised/rugged deployments were a dominant force of their own, but for the day-to-day device management for knowledge workers the options were to typically choose from a selection of Samsung devices the company was able offer and guarantee support.

Samsung and the Knox platform have come a long way; it happened to be Samsung tablets with which I got my first taste of device management combined with MaaS360, then under Fiberlink’s ownership! Being one of few OEMs who control pretty much their whole supply chain, Samsung have been able to be truly innovative in security throughout the entire device, hardware and software.

Fun fact – Samsung were even going to be the partner to help bring the first iteration of Android Enterprise, then Android for Work, to fruition before Google took it in a different direction.

As Android Enterprise has evolved, so too have Samsung, with their integration efforts to build their management platform atop Android Enterprise rather than alongside it.

They still won’t support zero-touch though. It’s KME (Knox Mobile Enrolment) or nothing. No matter how much Samsung and Google talk up initiatives like the Common Integration Library, for customers, it’s still two portals and unnecessary overhead for absolutely no reason other than, presumably, politics.

In any case, tools like KME, Knox Configure, Samsung’s extensive collection of restrictions and much more have clearly inspired Google over the years. Samsung were and continue to be a huge driver behind Android’s success in enterprise, and have marketed Android as an enterprise leader (they run adverts featuring enterprise use with Knox!) far more publicly than Google.

EMM management left a lot to be desired

#Remember containers, those per-EMM proprietary solutions that separated work and personal data? Good (bought by BlackBerry), MobileIron, AirWatch (VMware) and others still have these solutions up and running today, but they don’t compare to the native work profile implementation with Android Enterprise. Jack Madden has his own thoughts:

Work and personal data separation has always been a key issue in enterprise mobility. Before Android Enterprise, app-based separation features were the only viable route. During this time, there were at least a dozen attempts to provide Android devices with separation features built in directly at the device or OS level, but none of these early efforts took off. App-based solutions still have their place, but it was Android Enterprise work profiles that finally achieved the goal of a standard, device-based work and personal data separation framework that’s compatible with any app. This is a big deal.

Jack Madden, Executive Editor of BrianMadden.com

It of course wasn’t just work and personal data separation, I’ve talked about the fragmented approach to device admin management at length in various docs and articles, and how budget, time constraints, and opinions impacted heavily on what EMMs supported what features, particularly with so many bespoke APIs from so many OEMs to choose from.

If you had a selection of LG devices, for example, perhaps you’d go for SOTI or VMware, for Huawei maybe MobileIron or someone else. The relationships held between vendors and OEMs really heavily impacted ultimately how well these devices would be supported. Even Samsung, pretty much supported by all EMMs (as if they had a choice) would be better supported for some features by one EMM than another.

The introduction of Android Enterprise and those consistent management APIs really made things a lot easier for EMMs, but there were additional developments to come much later that truly puts the cherry on top.

Since MobileIron began managing Android devices with Froyo way back in 2010, we’ve witnessed a true sea change in the way Android devices are managed thanks to the introduction of Android Enterprise with Android 5.0.

Russell Mohr, Director of Sales Engineering, MobileIron

The F-word (Fragmentation)

#The word gets batted around still today, overwhelmingly more for clicks than anything else by the big tech sites, but when considering where Android is now compared to where it was even half a decade ago, there’s no comparison.

Sure, it’s easy to point at the distribution dashboard and feel like it makes the point by itself, but there’s always been more to it than just the reported major OS version.

Things like security updates (below) maintaining the safety of a device as much as 3 versions behind the latest Android release, Google’s separation of apps and services from Android’s core, allowing for Play Store updates at any time, or the recent introduction of Project Mainline to further modularise and update system components through Google Play.

For enterprise, adding Android Enterprise into the mix took the fragmented, no two OEMs (or even devices) the same management experience and streamlined it across all certified devices around the world.

Before Android Enterprise, the biggest challenge with managing Android devices was the fragmentation and lack of continuity between manufacturers. Standardizing the Android Enterprise platform across OEMs has enabled enterprise customers to deploy the devices they choose with the confidence that they will all work together.

Kevin Murray, Senior Product Manager, VMware

For enterprise, admins are often hesitant to embrace major version updates, not least without extensive testing that isn’t always easy to accomplish. Guaranteeing apps and services across a fleet of mixed manufacturers and their unique quirks can be a daunting task. Even if Android Enterprise brought with it management consistency, how individual developers build applications can lead to all sorts of problems when the OS version updates.

In my recent survey in fact, 8.5% of respondents say they either never want to see a letter upgrade, or don’t expect one. As long as the device continues to get security updates.

Organisations can’t stay on a particular Android version forever of course, as a pending major upgrade will often block the continued rollout of security updates, but certainly where a major upgrade isn’t a likelihood, the devices can remain protected for up to 3 years.

Gradual improvements

#The introduction of security updates

#Frequent security updates today are not only pretty much guaranteed across the big players in the ecosystem, they’re expected. With over 82% of respondents of my recent enterprise survey mandating updates within 90 days, and just under 39% (38.7%) of those requiring devices are updated monthly.

It wasn’t too many years ago, however, that security updates, or updates in any capacity, weren’t all that common, and in some cases organisations were lucky to see any updates at all depending on when in the device lifecycle chosen devices were deployed. The thought of a deploy-and-forget approach to Android is an uncomfortable one, but for many years – and even today, with >20% of organisations admitting to still managing Android 4.4.4 & lower, especially with rugged/dedicated devices – this is not unusual.

Google’s introduction of security updates was pivotal to the success of Android in the enterprise, offering backported support for up to 3 letters back and as such, ensured devices both new and old remain secure.

Since then Google have continued to further decouple components of Android for smoother, more frequent and more reliable updates, notably in Android 10 with project mainline offering the ability to update various modules of the OS via Google Play previously requiring system updates.

It’ll be super interesting to see what the next decade brings to the table concerning updates, and if Google one day get to a point where even major Android versions become unimportant, delivering new features through simple background updates that render full system updates mostly obsolete.

Big OEMs moved to Android

#As Android (and iOS as this naturally contributed also) continued to grow, competitors opting to run other operating systems saw their market share gradually decline into insignificance as the consumer market shifted. This video (from 1:27) demonstrates this wonderfully (and provides source for the comments below):

By 2012 both PalmOS and WebOS had fallen out of the spotlight. WebOS is still about, most recently I saw it in use on LG TVs, but doubt it’ll make any dramatic comeback. Palm today (under a different company licensing the Palm name) are using Android.

By 2014 Symbian, the once dominant mobile OS used by a number of OEMs, most notably Nokia, had dwindled into significance. Nokia’s devices business, later purchased by Microsoft, had already dabbled with the thought of Android on their Lumia line before Microsoft ultimately swooped in, bought them and ran them into the ground trying to make Windows Phone work, while other OEMs simply switched to Android.

The iconic Nokia brand didn’t stay away for too long, however. The smartphones you see today are now manufactured by Finnish company HMD Global, a company consisting notably of ex-Nokians and a few other folks, who license the Nokia brand for their devices. They’re doing extremely well in the market after opting, uniquely, to go all in on the Android One program and all of the benefits it brings.

From its start in 2016, HMD Global has focused on offering a pure Android experience with only the HMD camera app, and My Phone app for user support added.

In addition to benefits such as simple Out of Box Experience for enrolment and a strong battery life that is expected from a Nokia device, this has enabled Nokia smartphones to be the fastest to receive new Android OS versions across all devices, and to guarantee monthly security patches for all price points.

Andrej Sonkin, GM Enterprise Business, HMD Global

BlackBerryOS fell off the radar in 2017. BlackBerry went to the brink but bounced back with a renewed focus and devices (now made by TCL) running the Android OS. They also had another OS, QNX, on which BlackBerry 10 was based. This OS seems to have found a place in the IOT space.

Windows Mobile is still holding on with a 0.01% market share in 2019, though as mentioned above this is being slowly eroded.

These OEMs, and so many of the others across consumer, enterprise, rugged, and more who over the years have embraced Android as their OS of choice for the hardware they develop, have had an impact on the ecosystem not only through contributing to Android’s dominant global market share, but in the contributions back to the Android (open) source, the opinions and influence on the direction Android should travel and more. An open platform like Android is driven as much from outside as inside, and the experience industry behemoths have bestowed upon the platform cannot be overstated.

Encryption by default

#If you care to check your Android device (Settings > Security & Lockscreen > Encryption & credentials or thereabouts depending on your device) you’ll undoubtedly notice the device is encrypted.

If you fancy digging deeper, hook your device up to your computer and via ADB run:

adb shell getprop ro.crypto.type

If it returns block it’s Full Disk Encryption (FDE), whilst file is File Based Encryption (FBE). The more you know!

In any case, this wasn’t always how things were. It took until Android 6.0 before Google mandated encryption – FDE at the time (it was attempted with 5.0 but due to performance related issues this was pushed back). With Android 7.0 Google then introduced File Based Encryption, offering a much better UX for devices able to support the overhead at the time (far less of an issue today, unless you’re running very low-end hardware).

Today all devices should be encrypted out of the box. The better OEMs/hardware will leverage FBE, but at minimum FDE is required.

On-device security, Play Protect

#Google’s Play Protect suite of solutions includes the world’s largest anti-virus service, analysing 500,000 applications, and scanning over 50 billion on Google Play, on-device and crawling the web every day.

Google have had security solutions and services built into Android for a number of years, in 2017 though we saw the first steps towards turning everything from SafetyNet & PHA scanning, to consumer features like find my phone into it’s own, marketable product.

As with all solutions built on machine learning Play Protect’s capabilities have grown stronger over time, and with Google’s formation of the App Defense Alliance alongside market leaders in the MTD space, Play Protect will only continue to get better still.

Play Protect has helped to improve the negative perception of Android Security, and is often brought up in marketing and presentations.

Project Treble

#Talking of major updates higher up in the article, I would be remiss if I failed to touch on the profound impact Project Treble is having on major Android upgrades.

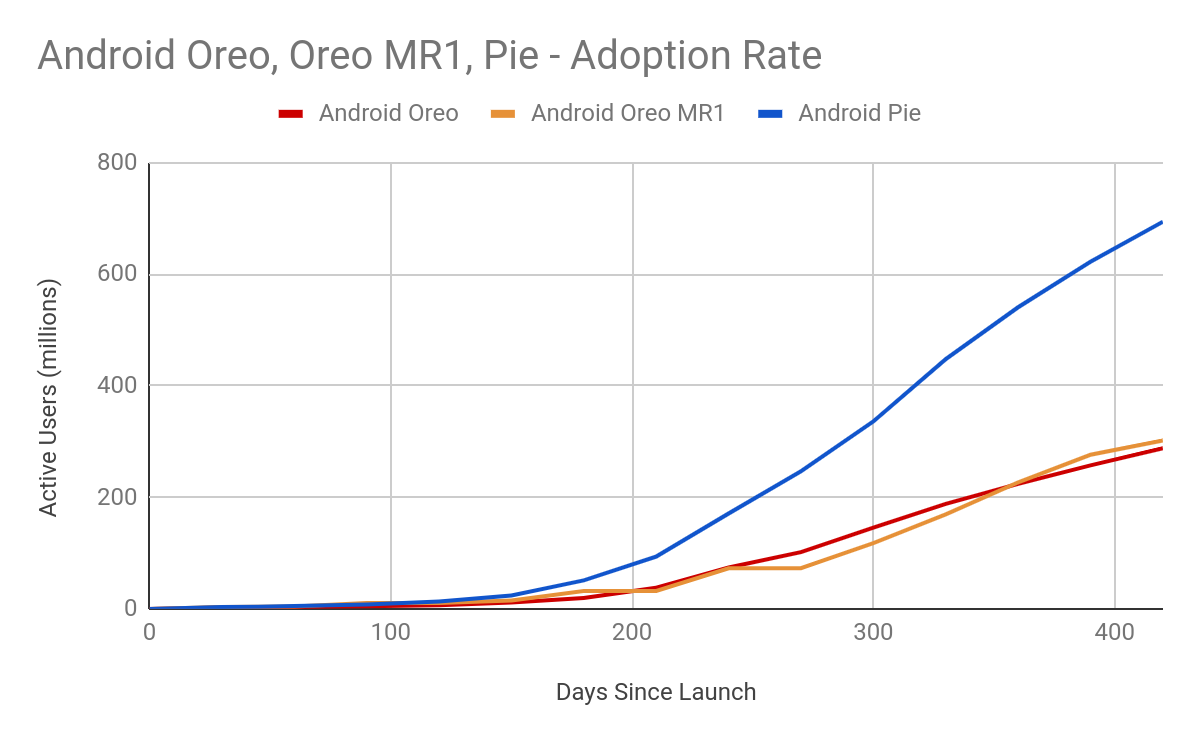

Introduced with Android 8.0, then tweaked for Android 9, Project Treble enabled the rapid development of version upgrades never before seen on the platform.

Disassociating the vendor layer from the Android framework meant where previously an OEM would need to update both the vendor implementation and the framework simultaneously to deliver an update, today the vendor implementation can remain untouched, offering OEMs easier, more rapid deployment of upgrades.

I quipped in my writeup of the Android Enterprise partner event 2018:

Again [Project Treble] is not new having launched with Android Oreo, but was thrust squarely into the spotlight at IO this year [..] when the launch of the Android P beta came to multiple devices at once for the first time in the history of Android.

It’s a significant achievement showing just how groundbreaking the feature is, bringing updates to devices faster and easier than ever before, whilst improving the overall security of devices in the process by isolating low-level components [..].

Of course that’s just my take, Google however back it up with facts:

In late July, 2018, just before Android 9 Pie was launched in AOSP, Android 8.0 (Oreo) accounted for 8.9% of the ecosystem. By comparison, in late August 2019, just before we launched Android 10, Android 9 (Pie) accounted for 22.6% of the ecosystem. This makes it the largest fraction of the ecosystem, and shows that Project Treble has had a positive effect on updatability.

Android developers blog, All About Updates: More Treble

Android developers blog, All About Updates: More Treble

Android developers blog, All About Updates: More Treble

Project Treble may not bring Android upgrade speed and distribution in line with iOS, but it has offered significant benefits to the platform which will undoubtedly only continue to show as Treble matures.

And, of course, Android Enterprise

#It’s only with Android Enterprise that we started considering Android as a viable platform for developing mobile security solutions.

Alessandro De Carli, Founder, Hypergate

Touched upon in various places already, Android Enterprise has had an indescribable effect on how the OS is perceived and used in enterprise over the last few years.

Android Enterprise has transformed Android from a typically perceived cheap, insecure device into a budget-scalable, flexible, customisable and trustworthy device in the enterprise world. The segregation of data, or containerisation is making its acceptance through security processes and by security officers much less painful that it used to be. Android Enterprise is, by far, the first recommendation we provide to our customers.

Jean-François Rigôt, Sr Tech. Consultant Mobile IT @ mobco

It wasn’t an overnight success by any means, starting out as an optional implementation in Android 5.0 (and an app before this.. but we won’t talk about that), it wouldn’t be until 6.0 that it started to become somewhat reliable, before reaching a reasonable maturity with 7.0.

There’s so much that can be said about Android Enterprise alone that it deserves it’s own doc, like this one, which I’ve been updating frequently since 2016. To summarise the incredible impact AE has had on the platform, solidifying it’s status as an OS for enterprise as much as anywhere else, here are some highlights:

A consistent UX, reliable management

#When comparing Android to almost any other mobile OS on the market it was clear how managing the platform could be challenging. While iOS and Windows Phone benefits from integrated management wholly designed and implemented by Apple and Microsoft respectively, Android had always relied on individual OEMs to figured out their own enterprise strategies.

Before Android enterprise, it was hard to predict what experience our customers might have when managing a diverse population of Android devices, but the consistency AE provides allows us to provided an elevated experience while reducing support costs because the outcome is now much more predictable.

Russell Mohr, Director of Sales Engineering, MobileIron

With the various management APIs available across OEMs, several proprietary provisioning flows and a general lack of consistency from one device to the next (even within OEMs) obviously one of the core objectives of Android Enterprise would be to fix this.

Google’s aim was to have every certified Android device on the market look and behave consistently when put under management.

Whether picking up a Pixel or an Xperia, a Galaxy or a Nokia, though the UI may have differed here and there, the underlying provisioning flows, the way a work profile is set up or how a device undertakes the disabling of the camera. It all happens using the same APIs, it’s reliable, it’s familiar, and it’s a million miles away from the management of old both for customers and EMM vendors.

With a standard set of APIs to use across any OEM, implementation is greatly streamlined for new functionality

Kevin Murray, Senior Product Manager, VMware

As Kevin states, the consistency and simplicity of Android Enterprise has equally had a profound impact on the vendors who implement these universal APIs; rather than having to work with each OEM independently, vendors now work directly with Google for the most part. With well documented APIs and simple escalation points the EMMs starting out today will have a tough time imagining how it used to be.

Unsurprisingly with customers being able to pick up most devices on the market and know they’ll work exactly as they need, the mandate for Samsung in enterprise as the only viable OEM has diminished:

Since the push forward with Android Enterprise gained momentum, I’ve noticed a marked decrease in the number of times I’ve heard “We only allow Samsung Android devices.” [Google’s] dedication to providing full management suites for both company owned and BYOD devices, as well as a middle ground (COPE) are admirable, and truly innovative for MDM/UEM.

Matt Shaver, Knowledge and Content Manager – MaaS360 by IBM

Not entirely though, although Google have successfully brought a base set of management capabilities to all GMS certified Android devices, they have equally encouraged differentiation; Samsung, along with Zebra and others are well known for their custom APIs, and in recent years have worked to fully integrate them to sit atop Android Enterprise. These continue to be available both as profile/policy options integrated into EMM consoles, and through newer initiatives such as OEMConfig (below).

No more Google account management

#Google accounts suck. They always have and they always will. The thought that so many organisations across the world were (and still are, stop it please) creating and managing accounts just for the sake of installing apps (including the DPC/EMM agent) on the device is crazy.

Not only for the fact that creating accounts is a pain and unnecessary overhead, but the myriad of caveats that go along with it:

You can’t have more than 10 devices enrolled per account

In reality you could and organisations did (do? I hope not any longer but it’d be ignorant to assume) do this, only to abruptly and with no warning find the account suspended. Whether that was after 20 devices or 2000, it was a real pain. I’d always mandated customers create an account per employee, or have the employee create it against their corp address and look after it themselves (on the basis it could be recovered by the org if required) but ultimately customers don’t list, or forget or any other reason.

If you share an account, you share more

I remember vividly getting a support request from a frantic field manager once upon a time who’d used the same Google account across a not-insignificant-number of devices and was calling to report that calendar invites, emails and more were being shared across the team fleet of tablets. It was around this time, in fact, that the rapid research into and deployment of an EMM solution – not that this would have been prevented by EMM necessarily, it was more the realisation of an obvious lack of visibility and control the IT department at the time.

FRP is easy to trigger, difficult to overcome

Since devices set up with device admin lacked the ability to disable factory reset protection (or whitelist accounts for it), all too often end-users would add an account not owned or controlled by the business only to have FRP enforced on its eventual return. Unfortunately there remains little to do other than sending the device off for repair in almost all cases, though through the years I’ve leveraged a few now-closed workarounds to avoid this in older versions of Android!

I reached out to my group, MobilePros, for any interesting DA Google account issues, Scott’s was with FRP:

We had a major issue with FRP locked devices, so much so that our recycling program was suffering pretty badly – this also caused an inventory issue for being able to redeploy devices to the field from stock. In the last two years after implementing Samsung KME and more recently AFE, we have nearly doubled our recycling for and of life devices and we’ve been able to be more picky about which devices can get redeployed to our users.

Scott, via MobilePros

Android Enterprise totally revamped the Google account experience, taking it entirely out of the hands of customers and making it just another step of the enrolment process.

Managed Google Play accounts are still, in effect, Google accounts. The difference is however:

- They aren’t authenticated (no user/pass to worry about)

- They’re created and deleted by the EMM automatically through the bind established between the EMM and Google

- They enable the silent, automatic installation of applications from Google Play

- They can be set as user or device accounts, with the latter overcoming the 10 device limitation

Read more about managed Google Play accounts.

Provisioning a device is a piece of cake

#Not even referencing zero-touch (which as of Android 10 is actually less zero-touch than ever before for end-users, but I digress). The provisioning methods gradually rolled out to Android over the last few years have transformed how corporate-owned devices are setup from out of the box (or a factory reset state):

Android 5: NFC

Android 6: DPC identifier/managed Google account

Android 7: QR code

Android 8: Zero-touch

Android 10: Zero-touch for work profile devices

The days of working through the entire setup wizard and, depending on the OEM, myriads of extra screens and account setup prompts, including the setup of the Google account, before landing on the home screen, opening Google Play, finding the relevant agent, downloading it and enrolling finally, universally (because some OEMs were working around this with proprietary setup flows), came to and end with the introduction of Android Enterprise.

When zero-touch later launched with 8.0 it once more drastically simplified provisioning by offering a true out-of-box experience for the devices that supported it. It certainly wasn’t an overnight success getting OEMs on board given even today zero-touch is optional for non-AER devices, but thankfully the ecosystem saw the vision and hopped on board pretty rapidly over the following two years.

DEP, Autopilot, and KME customers would understand the impact of being able to set up a zero-touch config to have devices find the right EMM and even fully automatically enrol straight out of the box, but even into 2020 this is still an unknown concept to many.

Also importantly, the introduction of zero-touch added a simple, persistent means for ensuring devices remained under management after a factory reset. This was already possible with some OEMs through various means but as with every other aspect of Android Enterprise, it brought the same capability to the wider ecosystem in a way that was easy to deploy and manage without individual EMMs or OEMs having to implement a means of supporting similar functionality. No longer could devices simply be reset/reflashed in an unauthorised manner to get out of management.

The only downside to zero-touch is it’s archaic reseller requirement. Samsung’s KME, Apple’s Enrolment Program, Windows Autopilot all support the grandfathering, or manually adding of devices, into the relevant portals.

Despite there being overwhelming support for the removal of this unnecessary restriction in the wider community, going into 2020 Google haven’t budged; a shame because I think it very much hinders adoption of the provisioning method globally.

Check out my docs on provisioning methods for more details on how these can be leveraged today.

Deployment scenarios galore

#As touched on above, before Android Enterprise organisations were forced to push a square peg through every other shaped hole. Bring your own device? Full device admin management. Corporate? Full device admin. Corporate with personal use? Full device admin.

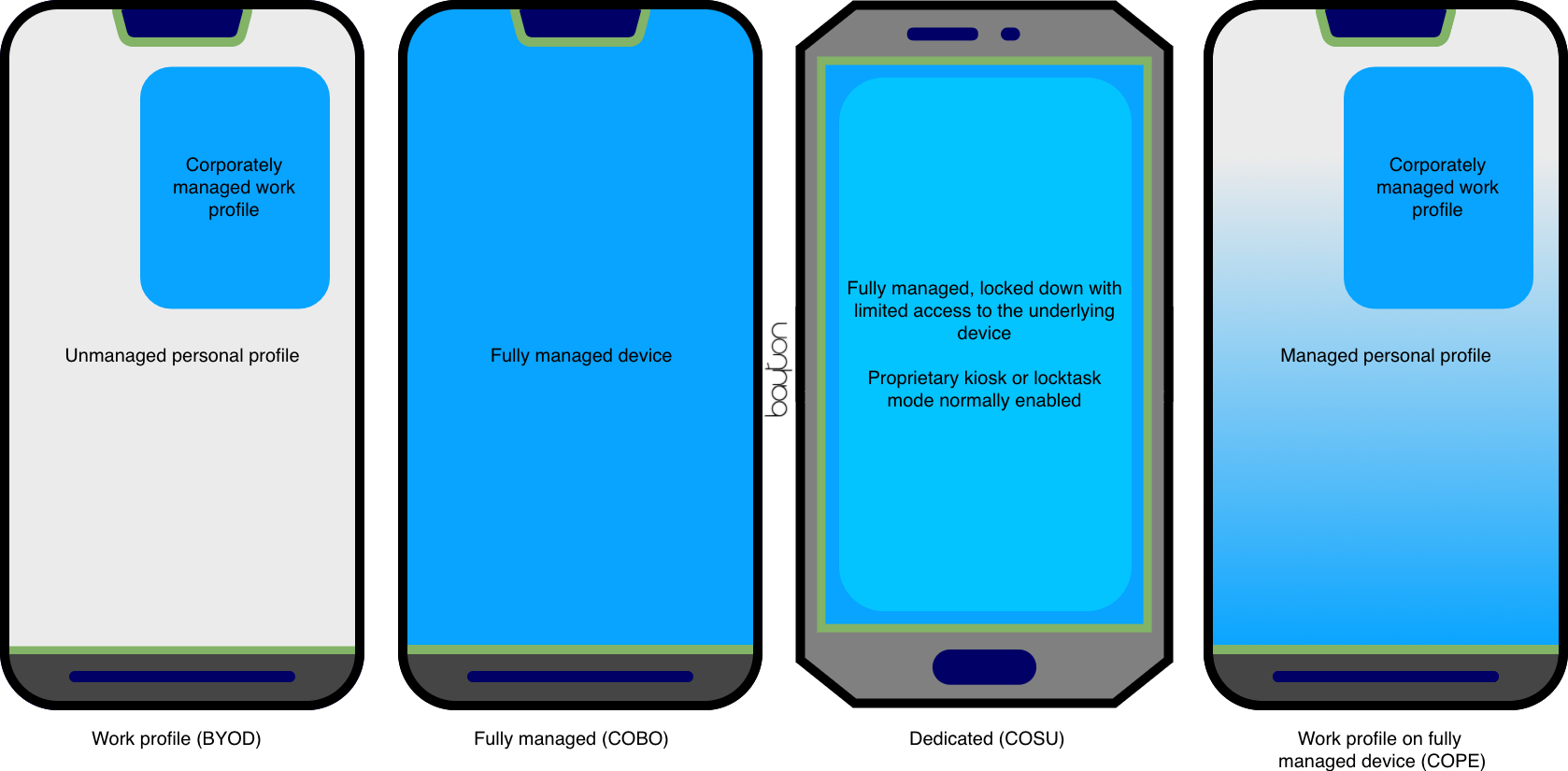

EMMs have come up with some very nice solutions over the years for separating data, preventing personal use and more in combination with OEM APIs, but it wasn’t until Android Enterprise there was a system-level differentiation between a device that is user owned with access to secure corporate data, a device that by default prevents personal use, including the removal of non-vital apps, a device for dedicated (kiosk) use and the flexibility to offer personal use on fully managed devices.

I’ve gone into detail on the different deployment scenarios, but for reference, here’s a handy graphic I use to explain it:

The two deployment scenarios I want to touch upon in particular are work profile and COPE, officially called work profiles on fully managed devices (which is still a rubbish, overly long name for COPE. Shortening it doesn’t really help either – WPoFMD hardly rolls off the tongue, and even playing with the order of the letters, which sort of defeats the purpose, only got me to FMWP, pronounced “fuhmewp”).

The two deployment scenarios I want to touch upon in particular are work profile and COPE, officially called work profiles on fully managed devices (which is still a rubbish, overly long name for COPE. Shortening it doesn’t really help either – WPoFMD hardly rolls off the tongue, and even playing with the order of the letters, which sort of defeats the purpose, only got me to FMWP, pronounced “fuhmewp”).

Work profile

Today when a personal device is onboarded, the end-user can know without a doubt their personal data, apps and other things they do with their devices remains private, while the work data sits completely separate, uniquely encrypted and protected within its own profile, the work profile.

When they’re finished working, users can turn the whole work profile off in one go, no need for the support of quiet hours within individual work apps, or to silence the whole phone to avoid disruptions from work. All apps suspend and consume zero resource on the device until reactivated when the work profile is turned back on.

The work profile offers one of the best features to come to enterprise for personal devices to date, and not only for end-users.

From the organisation’s perspective, it’s possible to ensure the device has a screenlock, to add a screenlock both to the device and the work profile separately (and uniquely), to ensure unknown sources can’t be enabled and that debugging is turned off. These few restrictions available offer just enough control for an organisation to determine the device secure enough to access corp data (and enforce best practices!) while not overstepping the privacy boundary.

Is it perfect? No.

- Users are limited to one work profile, so not viable for contractors or those who are otherwise forced to use multiple EMMs

- The UX concerning the split between work and personal apps was pretty confusing pre-9.0, and still gets people today (two apps, one with a badge and one without, it raises questions) in spite of the mostly-supported app launcher split

- There’s still limited overlap across profiles. Apps like Gmail can jump in-app between work and personal profiles without having to actively switch between the two versions of the app, while Google Contacts and Google Calendar support cross-profile search/visibility, these are but a few of the many enterprise apps in use today however

- Dual SIM management within the work profile is entirely non-existent, which is a odd when considering BYOD devices can have a secondary work-provided SIM that continues unhindered when the profile is disabled.

It is, regardless, so much better than an organisation holding complete control of a personal device, with visibility of many things done on the device any time of day or night. Privacy simply couldn’t be guaranteed with device administrator enrolments.

Work profiles on fully managed devices (COPE)

Despite being the closest deployment scenario to legacy DA management with corporate containerisation available, it took until Android 8.0 for work profiles on fully managed devices – or COPE, or COMP, or managed work profiles, or whatever else the deployment scenario has been called over the years – to debut on Android Enterprise.

Benefiting both from full device control due to it’s fully managed state, and profile-level separation of corporate data, WPoFMD offers the perfect deployment scenario where personal use is permitted on a corporate device without the DLP risks of mixing work and personal apps in-profile as would be the case if personal usage was permitted on a fully managed device.

It’s unfortunately still not supported universally today, over two years later, with a number of known EMM vendors in the ecosystem. The likes of SOTI, MaaS360, Intune and even Google themselves with their Android Management API still don’t support COPE, leaving organisations around the world needlessly waiting, or working around the requirement by opting to deploy work profile only and forego device-level management.

Those EMMs who do support it could improve the UX more still by following in the footsteps of Citrix to enable support for enterprise wipe, or offering the ability to migrate between fully managed and WPoFMD, a feature that should be easy enough to implement, but is yet to see traction.

Android Enterprise Recommended

#In 2018 Google launched Android Enterprise Recommended. Initially for devices and later rolling out to EMMs, MSPs and at some point soon may expand it once more to Carriers.

AER takes all the work Google have put into the ecosystem to date, and invites partners to apply for the opportunity to have their devices, solutions or companies validated to align with Googles recommendations, requirements and best practices. I’ve written about it in more detail here.

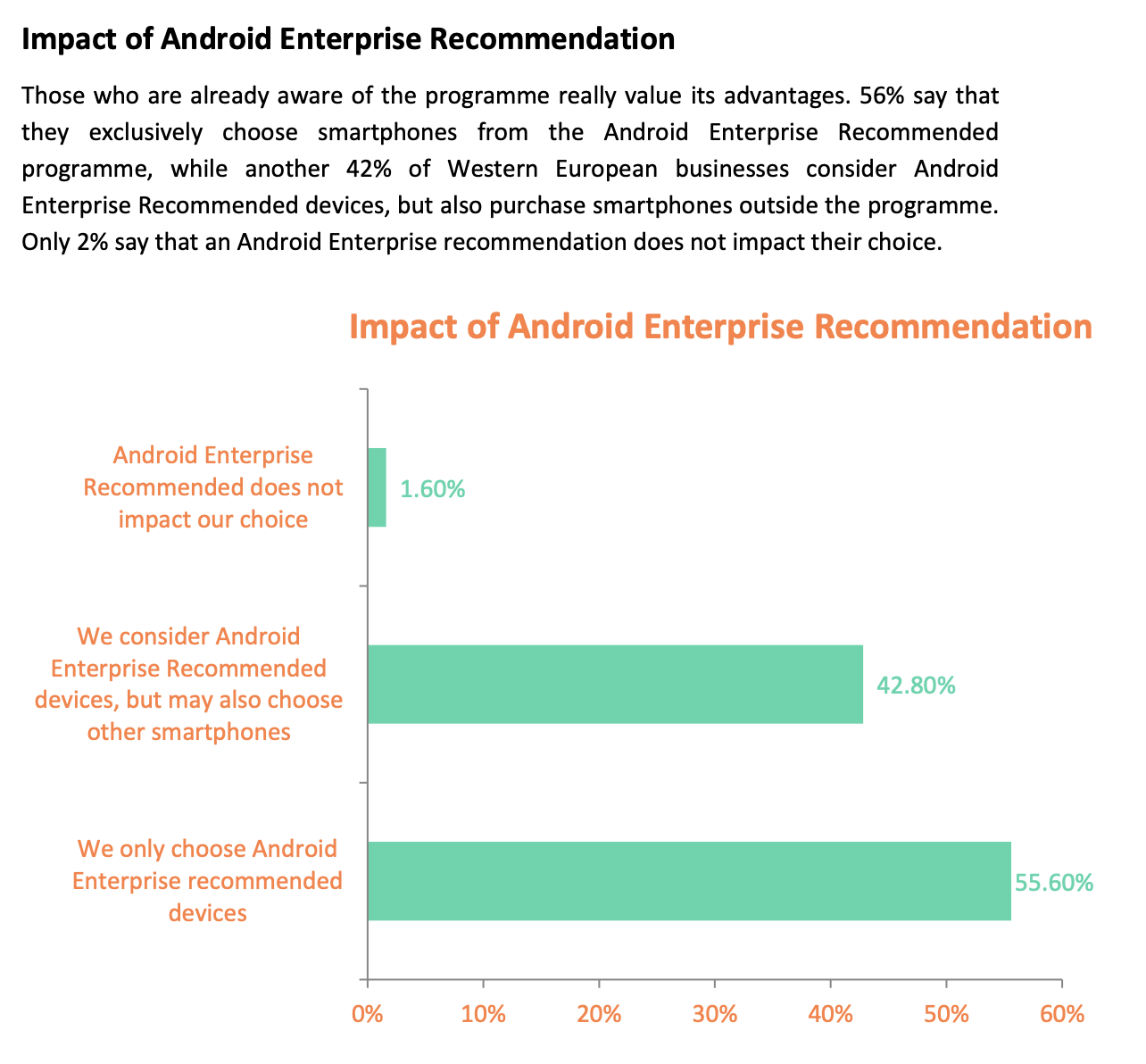

It adds further credibility to the validated entity, essentially saying yes, Google recommends this as an enterprise-ready device/platform/company and it has had an extraordinary effect on the market.

HMD Global undertook a study in 2018 that demonstrated the importance of AER to organisations, with 56% of respondents mandating a device should be Android Enterprise Recommended:

HMD Global B2B Smartphone Purchase Survey 2018

HMD Global B2B Smartphone Purchase Survey 2018

In my own survey in 2019, 72% of organisations who took part considered AER to be important or very important when purchasing devices. 44.2% consider AER status of an MSP or VAR to be a deciding factor (16.9% of that 44.2% consider AER mandatory in order to work with an MSP), and 48.6% of respondents agreed that in gaining AER status, their EMM has improved feature availability, management reliability and more.

However you choose to look at it, be that customers who feel they get the best experience by seeking out an AER device, or EMM vendors who improve their solutions to meet Google’s recommendations and requirements, the Android Enterprise Recommended program has, and continues to raise the standards across all ecosystem partners.

OEMConfig

#This feature is one of the best gifts that Android Enterprise could offer to MDMs. It takes off a lot of work from our hands because we don’t need to spend time developing features for various vendors anymore.

Public statement by Vipin Govind, Android Systems Engineer, Hexnode

Undoubtedly my favourite Android Enterprise feature to date, the implications of OEMConfig on the entire ecosystem are incredible. I’m absolutely not alone in my feelings towards the feature, as when I asked a few people for their opinion on the best feature of AE to date, I received the following:

OEMConfig has been a game-changing feature that has allowed MobileIron to get out of the game of supporting custom API’s from many different vendors and freeing us up to focus on truly important aspects of Android management like delivering a world class end-user experience.

Russell Mohr, Director of Sales Engineering, MobileIron

Without picking [a feature] that’s at the very heart of AE like Fully managed mode, I think Managed Configuration and specifically OEM Config will make the biggest impact across the entire ecosystem. As Android moves more towards native functionality, the ability to differentiate becomes increasingly important for device manufacturers and EMMs. Providing a standard way to implement differentiation for OEMs allows customers to get features more quickly while each other player in the management of the device can focus on what they do best.

Kevin Murray, Senior Product Manager, VMware

It absolutely makes sense that EMM vendors are excited about OEMConfig, but OEMs benefit as much if not more by moving from the legacy approach of EMM API integration to a wholly owned and controlled alternative.

When working with EMMs there are always time constraints, budget restraints, PMs who have their own priorities and opinions on what should and should not be incorporated into their solutions. Before EMMs are finished implementing one set of APIs, OEMs are working on new and updated features.

It’s slow, cumbersome, very likely frustrating also.

OEMConfig takes so much of this burden away from both sides. The EMMs no longer have to implement bespoke APIs, and the OEMs have complete control over what APIs are available to all EMMs, universally, who support managed configurations (and nested configurations). OEMs can add new features daily if so inclined, and as soon as the OEMConfig app is published, customers across the world see it almost immediately.

It is utterly incredible the impact this will have on the ecosystem, or arguably already is having given Zebra, Samsung, Sony, DataLogic, Honeywell and undoubtedly many more all support OEMConfig already. Even OEMs who in the past may not have wanted to dabble with custom APIs may choose to do so now that it’s so simple, without any of the legacy overhead of years gone by, and in doing so it fulfils Google’s ambition to embrace value-added functionality over and above Android Enterprise base APIs.

It is an absolute win for all involved.

The Android Enterprise ecosystem impact

#Without Android Enterprise the ecosystem would be drastically different. Few OEMs would be singing from the same hymn sheet, fragmentation would have remained rife for support across EMM/UEMs and just a few market leaders would dominate the enterprise space with little competition.

Not to mention the perception of Android would likely still be suffering around security and usability, PHAs would have far more control over modern devices on permission-based attacks (my reasoning being without AE, DA deprecation wouldn’t have happened) and probably more.

How did we close out 2019?

#Version stats

#As Google’s official distribution dashboard has been broken for about 20% of the decade in itself, there’s no really good data to show how Android 10 has been adopted over the last few months.

Turning to other sources though, like the stats from my own site over the year, it has similarities to other recently published stats the wider internet has been talking about recently.

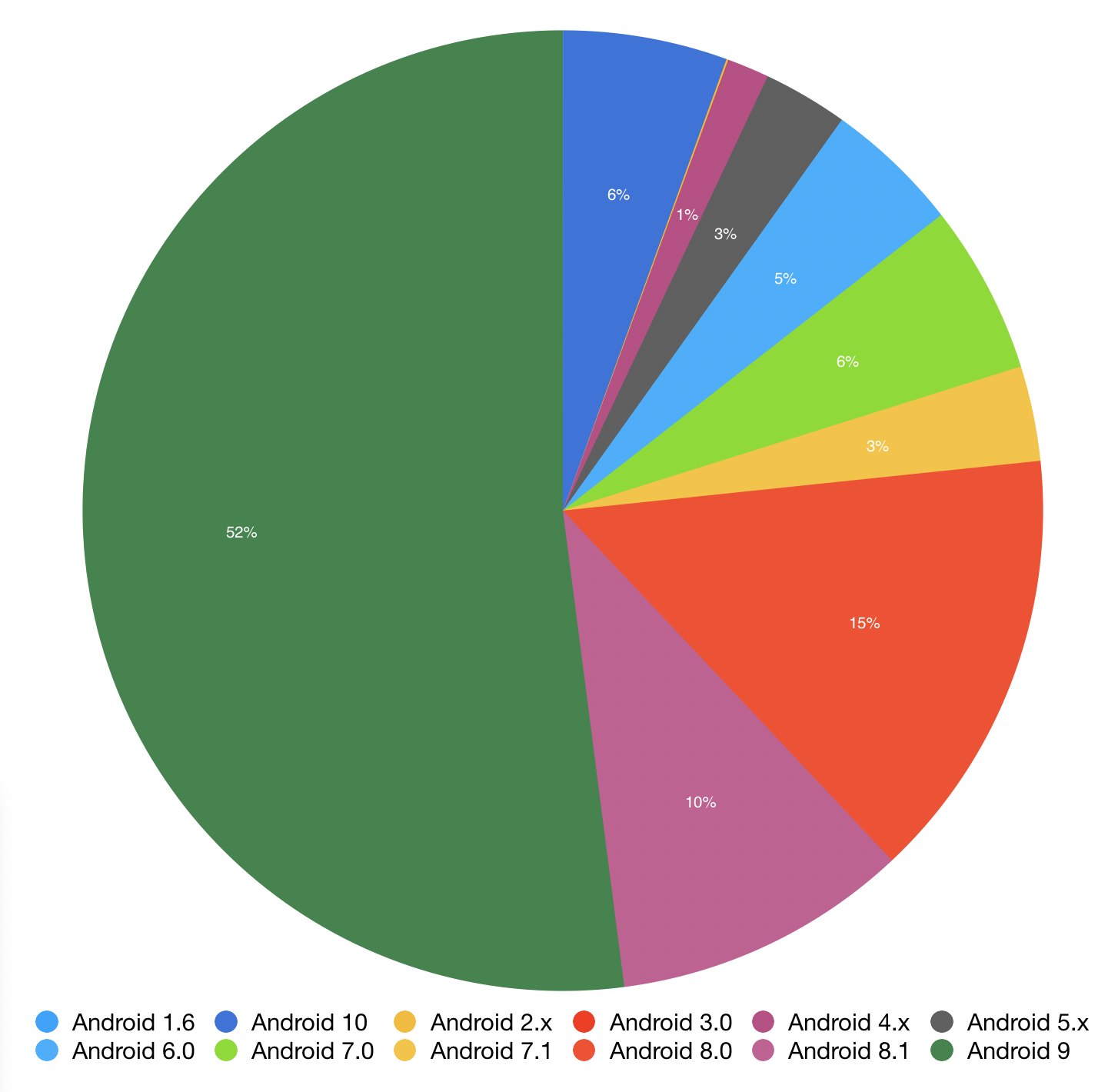

Pie is dominating the chart (green) with 52% of all mobile visits this year, which in itself is incredible; equally impressive however is Android 10 (darker blue, top) contributing 6% of visits.

Pie is dominating the chart (green) with 52% of all mobile visits this year, which in itself is incredible; equally impressive however is Android 10 (darker blue, top) contributing 6% of visits.

6% might not seem much, but it sits higher than all versions below Nougat (also at 6% with 7.0, 9% if including 7.1) and Oreo 8.1 (but not 8.0, interestingly).

That Android 7.1 (which officially dropped out of security update support last November) and lower contributed to >18% of visits doesn’t fill me with joy, but the numbers of old devices are slowly decreasing.

Back to Android 10, compared to years gone when the latest version of the OS is in the single digits more than half a year after release, as opposed to nearing double digits in only 4 months, the work of initiatives like Project Treble have had immense influence over how rapidly devices receive the newest letter upgrades.

Desserts are no more

#With Android 10, the last release of the decade, Google opted to forego desserts in favour for a simple, straightforward number going into 2020.

While Google have confirmed letters would still be used internally, all future updates to Android will be number based. No more quirky desserts!

Device Admin APIs are deprecated

#After over two years of talking about it, DA APIs were officially deprecated in 2019. The so many issues associated with DA will slowly now become a thing of the past as Google continue to deprecate APIs.

But more than this, the deadline for Android Enterprise Recommended EMMs to bump up minimum supported API to Android 10 (API 29) was by January 2020. At that point any Android 10 device enrolling into these EMMs would no longer be able to properly manage legacy enrolled devices.

At the time of writing, both MobileIron, who have really led by example for Android Enterprise support of features over the last few years, and Softbank’s Business Center EMM have updated their DPCs to target Android 10. No doubt others will soon follow.

The sooner DA goes away, the better. Going into 2020 however that is still a very distant future!

The days of building a custom DPC are over

#Google are super intent on pushing forward with the Android Management API (AMAPI), despite it’s late development and lack of features. Visiting the EMM community registration page for the Play EMM API shows it’s no longer possible to even register with the EMM community for a custom DPC based solution.

That would be a non-issue if AMAPI was a drop-in replacement for Play EMM APIs with comparable features and flexibility, but it isn’t as yet. AMAPI is getting there but still has so far to go and means we’ve probably got a long wait before it comes close to being on-par with the custom DPC leaders (VMware, MobileIron, etc). We lack COPE (work profiles on fully managed devices), granular control of cross-profile sharing intents, proper location control, ephemeral user support, system app management, and undoubtedly plenty more I haven’t had use cases for to learn they aren’t supported.

The end-goal is great, AMAPI offering all the benefits outlined in many other articles and docs I’ve written will do wonders for the future of Android management – the minimal vendor development, zero-day support for new features, the native look and feel of a device managed through AMAPI, and more.. Until then, though, we sit and wait while Google pop out incremental updates on a monthly basis while lacking basic features custom DPC solutions have offered for years.

Hopefully in 2020 it’ll get to a point where choosing between AMAPI or Play EMM API – for existing vendors at least given that choice has now been taken away from the wider ecosystem – will be a no-brainer, and AMAPI will rapidly get far ahead of Play EMM API in functionality. It goes without saying that by the time the 20’s draw to a close most will likely forget there was even a time when anything other than AMAPI was used.

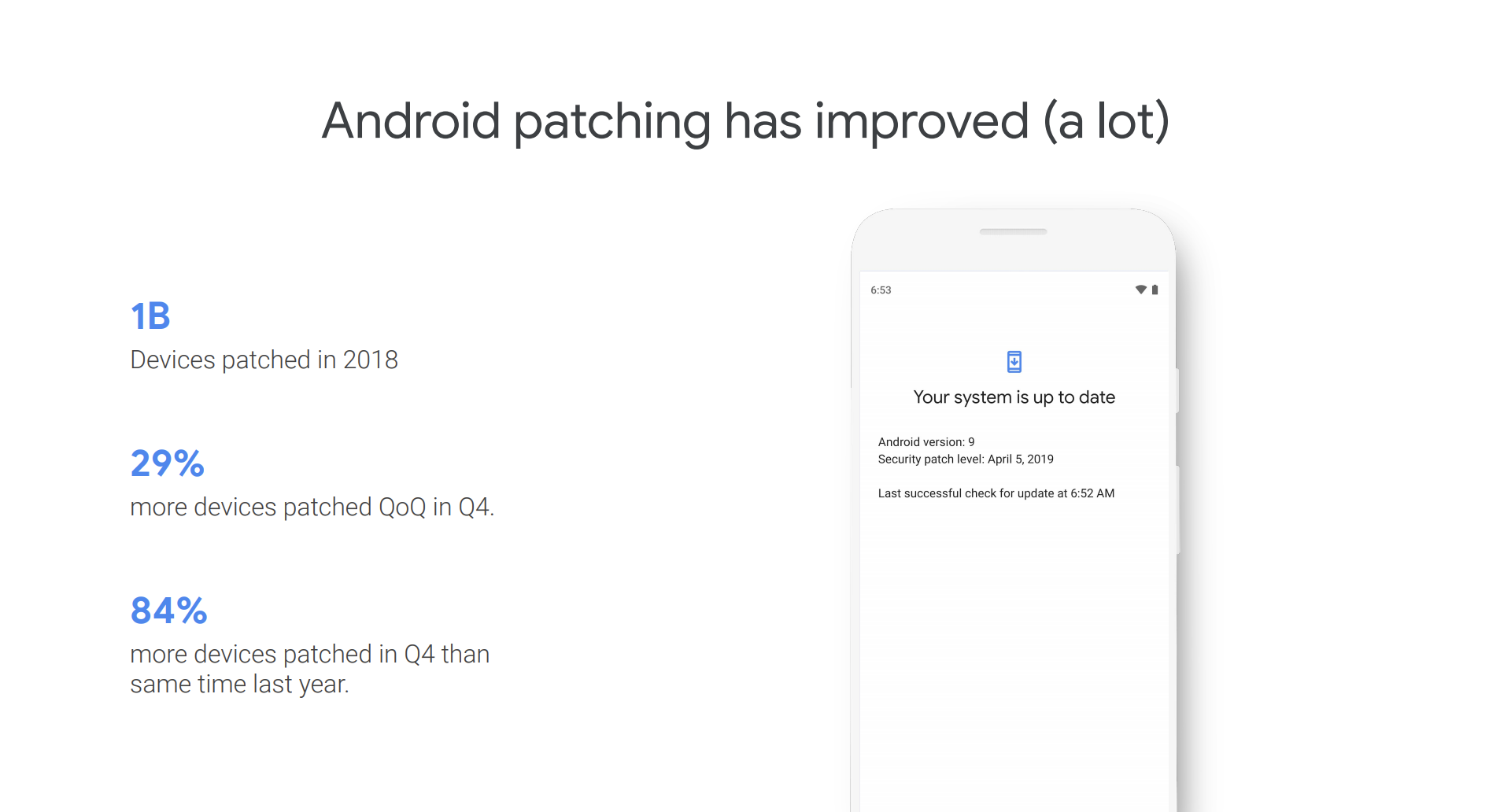

More devices than ever before are patched and secure

#It is extremely likely your Android device, whether bought for business or as a consumer, is benefiting from the enormous drive to get OEMs patching more frequently and for longer.

If you’re using a Nokia, counterpoint research shows you’re also most likely to be running the latest version of Android.

With the likes of Android Enterprise Recommended requiring 3 years of security updates, the Android One program requiring them every 30 days, and more and more OEMs taking the enterprise market and it’s requirements far more seriously over recent years, the knock-on effect is a more secure, more frequently updated ecosystem for everyone.

To the next decade

#It has been fascinating to watch Android evolve over the years and the influence so many ecosystem partners have had on it, even more-so given the profound impact Android has had on my career over the last 10 (and longer) years; without Android I’d still probably be doing Disaster Recovery!

As can be imagined there are so many topics I haven’t touched on, be that fully or at all. As much as I’d like to carry on rambling, I wouldn’t be able to cover off all of the topics readers would be expecting to see if I tried!

Finally, if 2020 is the year you’re thinking about adopting Android, take a look at why Gartner have ranked Android highest in the category for security controls, kernel security and more the last couple of years, and check out this article on why Android is the perfect OS for business. If you’re looking to move away from device admin with your existing legacy-managed fleet ahead of Android 10 adoption, check out my doc on considerations when migrating.

Here’s to the next decade, and a very belated Happy New Year!

Articles

2026

2025

- Google Play Protect is now the custom DPC gatekeeper, and everyone is a threat by default

- 12 deliveries of AE-mas (What shipped in Android Enterprise in 2025)

- The 12 AE requests of Christmas (2025 Edition)

- RCS Archival and you: clearing up the misconceptions

- Device Trust from Android Enterprise: What it is and how it works (hands-on)

- Android developer verification: what this means for consumers and enterprise

- AMAPI finally supports direct APK installation, this is how it works

- The Android Management API doesn't support pulling managed properties (config) from app tracks. Here's how to work around it

- Hands-on with CVE-2025-22442, a work profile sideloading vulnerability affecting most Android devices today

- AAB support for private apps in the managed Google Play iFrame is coming, take a first look here

- What's new (so far) for enterprise in Android 16

2024

- Android 15: What's new for enterprise?

- How Goto's acquisition of Miradore is eroding a once-promising MDM solution

- Google Play Protect no longer sends sideloaded applications for scanning on enterprise-managed devices

- Mobile Pros is moving to Discord

- Avoid another CrowdStrike takedown: Two approaches to replacing Windows

- Introducing MANAGED SETTINGS

- I'm joining NinjaOne

- Samsung announces Knox SDK restrictions for Android 15

- What's new (so far) for enterprise in Android 15

- Google quietly introduces new quotas for unvalidated AMAPI use

- What is Play Auto Install (PAI) in Android and how does it work?

- AMAPI publicly adds support for DPC migration

- How do Android devices become certified?

2023

- Mute @channel & @here notifications in Slack

- A guide to raising better support requests

- Ask Jason: How should we manage security and/or OS updates for our devices?

- Pixel 8 series launches with 7 years of software support

- Android's work profile behaviour has been reverted in 14 beta 5.3

- Fairphone raises the bar with commitment to Android updates

- Product files: The DoorDash T8

- Android's work profile gets a major upgrade in 14

- Google's inactive account policy may not impact Android Enterprise customers

- Product files: Alternative form factors and power solutions

- What's new in Android 14 for enterprise

- Introducing Micro Mobility

- Android Enterprise: A refresher

2022

- What I'd like to see from Android Enterprise in 2023

- Thoughts on Android 12's password complexity changes

- Google Play target API requirements & impact on enterprise applications

- Sunsetting Discuss comment platform

- Google publishes differences between Android and Android Go

- Android Go & EMM support

- Relaunching bayton.org

- AER dropped the 3/5 year update mandate with Android 11, where are we now?

- I made a bet with Google (and lost)

2020

- Product files: Building Android devices

- Google announce big changes to zero-touch

- VMware announces end of support for Device Admin

- Google launch the Android Enterprise Help Community

- Watch: An Android Enterprise discussion with Hypergate

- Listen again: BM podcast #144 - Jason Bayton & Russ Mohr talk Android!

- Google's Android Management API will soon support COPE

- Android Enterprise in 11: Google reduces visibility and control with COPE to bolster privacy.

- The decade that redefined Android in the enterprise

2019

- Why Intune doesn't support Android Enterprise COPE

- VMware WS1 UEM 1908 supports Android Enterprise enrolments on closed networks and AOSP devices

- The Bayton 2019 Android Enterprise experience survey

- Android Enterprise Partner Summit 2019 highlights

- The Huawei ban and Enterprise: what now?

- Dabbling with Android Enterprise in Q beta 3

- Why I moved from Google WiFi to Netgear Orbi

- I'm joining Social Mobile as Director of Android Innovation

- Android Enterprise in Q/10: features and clarity on DA deprecation

- MWC 2019: Mid-range devices excel, 5G everything, form-factors galore and Android Enterprise

- UEM tools managing Android-powered cars

- Joining the Android Enterprise Experts community

- February was an interesting month for OEMConfig

- Google launch Android Enterprise Recommended for Managed Service Providers

- Migrating from Windows 10 Mobile? Here's why you should consider Android

- AER expands: Android Enterprise Recommended for EMMs

- What I'd like to see from Android Enterprise in 2019

2018

- My top Android apps in 2018

- Year in review: 2018

- MobileIron Cloud R58 supports Android Enterprise fully managed devices with work profiles

- Hands on with the Huawei Mate 20 Pro

- Workspace ONE UEM 1810 introduces support for Android Enterprise fully managed devices with work profiles

- G Suite no longer prevents Android data leakage by default

- Live: Huawei Mate series launch

- How to sideload the Digital Wellbeing beta on Pie

- How to manually update the Nokia 7 Plus to Android Pie

- Hands on with the BQ Aquaris X2 Pro

- Hands on with Sony OEMConfig

- The state of Android Enterprise in 2018

- BYOD & Privacy: Don’t settle for legacy Android management in 2018

- Connecting two Synologies via SSH using public and private key authentication

- How to update Rsync on Mac OS Mojave and High Sierra

- Intune gains support for Android Enterprise COSU deployments

- Android Enterprise Recommended: HMD Global launch the Nokia 3.1 and Nokia 5.1

- Android Enterprise Partner Summit 2018 highlights

- Live: MobileIron LIVE! 2018

- Android Enterprise first: AirWatch 9.4 lands with a new name and focus

- Live: Android Enterprise Partner Summit 2018

- Samsung, Oreo and an inconsistent Android Enterprise UX

- MobileIron launch Android Enterprise work profiles on fully managed devices

- Android P demonstrates Google's focus on the enterprise

- An introduction to managed Google Play

- MWC 2018: Android One, Oreo Go, Android Enterprise Recommended & Android Enterprise

- Enterprise ready: Google launch Android Enterprise Recommended

2017

- Year in review: 2017

- Google is deprecating device admin in favour of Android Enterprise

- Hands on with the Sony Xperia XZ1 Compact

- Moto C Plus giveaway

- The state of Android Enterprise in 2017

- Samsung launched a Note 8 for enterprise

- MobileIron officially supports Android Enterprise QR code provisioning

- Android zero-touch enrolment has landed

- MobileIron unofficially supports QR provisioning for Android Enterprise work-managed devices, this is how I found it

- Hands on with the Nokia 3

- Experimenting with clustering and data replication in Nextcloud with MariaDB Galera and SyncThing

- Introducing documentation on bayton.org

- Goodbye Alexa, Hey Google: Hands on with the Google Home

- Restricting access to Exchange ActiveSync

- What is Mobile Device Management?

- 8 tips for a successful EMM deployment

- Long-term update: the fitlet-RM, a fanless industrial mini PC by Compulab

- First look: the FreedomPop V7

- Vault7 and the CIA: This is why we need EMM

- What is Android Enterprise (Android for Work) and why is it used?

- Introducing night mode on bayton.org

- What is iOS Supervision and why is it used?

- Hands on with the Galaxy TabPro S

- Introducing Nextcloud demo servers

- Part 4 - Project Obsidian: Obsidian is dead, long live Obsidian

2016

- My top Android apps 2016

- Hands on with the Linx 12V64

- Wandera review 2016: 2 years on

- Deploying MobileIron 9.1+ on KVM

- Hands on with the Nextcloud Box

- How a promoted tweet landed me on Finnish national news

- Using RWG Mobile for simple, cross-device centralised voicemail

- Part 3 – Project Obsidian: A change, data migration day 1 and build day 2

- Hands on: fitlet-RM, a fanless industrial mini PC by Compulab

- Part 2 - Project Obsidian: Build day 1

- Part 1 - Project Obsidian: Objectives & parts list

- Part 0 - Project Obsidian: Low power NAS & container server

- 5 Android apps improving my Chromebook experience

- First look: Android apps on ChromeOS

- Competition: Win 3 months of free VPS/Container hosting - Closed!

- ElasticHosts review

- ElasticHosts: Cloud Storage vs Folders, what's the difference?

- Adding bash completion to LXD

- Android N: First look & hands-on

- Springs.io - Container hosting at container prices

- Apple vs the FBI: This is why we need MDM

- Miradore Online MDM: Expanding management with subscriptions

- Lenovo Yoga 300 (11IBY) hard drive upgrade

- I bought a Lenovo Yoga 300, this is why I'm sending it back

- Restricting access to Exchange ActiveSync

- Switching to HTTPS on WordPress

2015

2014

- Is CYOD the answer to the BYOD headache?

- BYOD Management: Yes, we can wipe your phone

- A fortnight with Android Wear: LG G Watch review

- First look: Miradore Online free MDM

- Hands on: A weekend with Google Glass

- A month with Wandera Mobile Gateway

- Final thoughts: Dell Venue Pro 11 (Atom)

- Thoughts on BYOD

- Will 2014 bring better battery life?

- My year in review: Bayton.org

- The best purchase I've ever made? A Moto G for my father

2013

2012

- My Top Android Apps 12/12

- The Nexus 7 saga: Resolved

- Recycling Caps Lock into something useful - Ubuntu (12.04)

- The Nexus 7 saga continues

- From Wows to Woes: Why I won't be recommending a Nexus7 any time soon.

- Nexus7: What you need to know

- Why I disabled dlvr.it links on Facebook

- HTC Sense: Changing the lockscreen icons from within ADW

2011

- Push your Google+ posts to Twitter and Facebook

- Using multiple accounts with Google.

- The "Wn-R48" (Windows on the Cr-48)

- Want a Google+ invite?

- Publishing to external sources from Google+

- Dell Streak review. The Phone/Tablet Hybrid

- BlueInput: The Bluetooth HID driver Google forgot to include

- Pushing Buzz to Twitter with dlvr.it

- Managing your social outreach with dlvr.it

- When Awe met Some. The Cr-48 and Gnome3.

- Living with Google's Cr-48 and the cloud.

- Downtime 23-25/04/2011

- Are you practising "safe surfing"?

- The Virtualbox bug: "Cannot access the kernel driver" in Windows

- Putting tech into perspective

2010

- Have a Google Buzz Christmas

- Root a G1 running Android 1.6 without recovery!

- Windows 7 display issues on old Dell desktops

- Google added the Apps flexibility we've been waiting for!

- Part I: My 3 step program for moving to Google Apps

- Downloading torrents

- Completing the Buzz experience for Google Maps Mobile

- Quicktip: Trial Google Apps

- Quicktip: Save internet images fast

- Turn your desktop 3D!

- Part III - Device not compatible - Skype on 3

- Swype not compatible? ShapeWriter!

- Don't wait, get Swype now!

- HideIP VPN. Finally!

- Google enables Wave for Apps domains

- Aspire One touch screen

- Streamline XP into Ubuntu

- Edit a PDF with Zamzar

- Google offering Gmail addresses in the UK

- Google Wave: Revolutionising blogs!

- Hexxeh's Google Chrome OS builds

- Update: Buzz on Windows Mobile

- Alternatives to Internet Explorer

- Wordress 3.0 is coming!

- Skype for WM alternatives

- Browsing on a (data) budget? Opera!

- Buzz on unsupported mobiles

- Buzz on your desktop

- What's all the Buzz?

- Part II: Device not compatible - Skype on 3

- Part I - Device not compatible - Skype on 3

- Dreamscene on Windows 7

- Free Skype with 3? There's a catch..